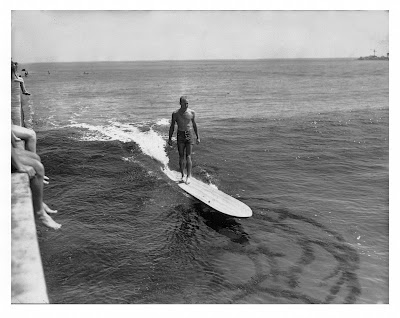

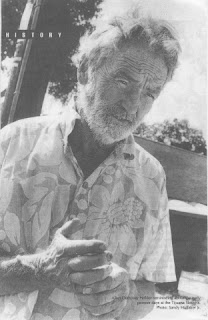

Allen "Dempsey" Holder, who started and lead it all.

Image courtesy of Tom Keck

The hardcore surfers who rode the Tijuana Sloughs, south of Imperial Beach, California, right next to the international border with Mexico, are unquestionably the most unknown of

California’s standout surfers of the 1940s and even later.

The Tijuana Sloughs was the site of California’s first assault on big surf. It began with body surfing and riding soup on very crude equipment – even “wooden doors”

– in the late 1930s. After World War II, Sloughs big wave surfers grew from a handful of surfers riding planks to a couple dozen locals and visitors from all over Southern California riding redwood/balsa’s and

then, finally, Simmons “machines.”

Although many of those who rode the Sloughs would go on to find more consistent big wave surf in the Hawaiian Islands, the Tijuana Sloughs remained California’s premiere big

wave spot until Mavericks – outside Pillar Point Harbor, just north of Half Moon Bay – was regularly surfed at the beginning of 1990.

Note:

Additional noteworthy writings on The Sloughs include:

-- Timothy Connor Sullivan's excerpt from "Wild Sea," 1993: https://www.facebook.com/share/18yknjFhBt/

-- Kimball Dodds: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1Ajn6BvZfU/

Geology & Topology

Bank Wright, in Surfing California, referred to the Tijuana Sloughs – located at the mouth of the Tijuana River, on the border between the United States and Mexico – as “A spooky, big-wave break.”1

From the late 1930s onward, it became known first and foremost for its winter surf of size. There are three main breaks, the Outer Peak, the Middle Peak and the Inside Peak. A spot that breaks rarely is what some old timers

have called the “Mystic Peak” or “Mystery Break” which is even further out than the Outer Peak and only breaks in abnormally huge swells.2

The Tijuana River, as it enters the Pacific Ocean, is an inter tidal coastal estuary on the international border. Three-quarters of its 1,735 square mile watershed is in Mexico.

The salt-marsh dominated habitat is characterized by extremely variable stream flow, with extended periods of drought interrupted by heavy floods during wet years. The estuary – what is now the 2,531 acres of tidal wetlands

known as the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve – is the largest salt water marsh in Southern California.3

The Tijuana Rivermouth is ancient, having formed during glacial times when heap stones were deposited as far out as a mile from shore. During the last glacial melt, the river’s

mouth became a massive reef and was covered up with ocean. Kelp beds now grow on the stone deposits, over a mile out.4

The Tijuana River begins at the confluence of the Rio Ala Mar and Arroyo Las Palmas, eleven miles southeast of the city of Tijuana, Baja California. It enters the United States just

west of the city of San Ysidro and flows northwesterly 5.3 miles through the Tijuana River Valley into the Pacific Ocean.

The lower Tijuana River Valley encompasses 4,800 acres; a small patch of open space between two major metropolitan centers, San Diego and Tijuana. The valley is host to agricultural

farms and horse ranches. The estuary itself is about three miles long and one and a half miles wide. It encompasses 1,100 acres that include salt marshes and tide channels.

The Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve, with its unique location on the Pacific Flyway, attracts many species of birds. Over 370 species have been sited in the estuary

and the Tijuana River Valley. About fifty species are resident birds, the rest are migratory. There are six endangered species of birds which use the estuary: the California least tern, the western snowy plover, brown pelican,

least bell’s vireo, light footed clapper rail, American peregrine falcon, and the belding’s savannah sparrow.5

Sloughs Rider Jim Voit wrote about the topography of the Sloughs:

“I have dived in the Sloughs area and seen eelgrass and rocks in the shallow waters. In 20+ feet of water the scene looks a lot like the desert at the foot of a canyon –

lots of volleyball sized boulders and almost no vegetation. Further out, I have heard there is kelp. I have never seen “reefs” there of the kind seen at La Jolla, Sunset Cliffs, Cardiff, Del Mar, and other places

along the coastline of the San Diego area.

“The location of rocks in the Sloughs area can be inferred from where the lobster fisherman set their traps, and that is generally in the area north of the Sloughs mouth and

south of Imperial Beach Avenue. Bobby Wilder, a summer guard there, once dived with tanks in about 30 feet of water off Elm Avenue to determine why a lobster trap was set there, on what we thought was a sand bottom. He found

a Navy F4U resting on the sandy bottom, with lobsters sheltered between the ribs of the wings. So the fishermen are good at finding lobsters, and where there are lobsters, there are rocks (or airplanes).

“The bottom around the end of the pier [in Imperial Beach] is sand, off the Navy radio station (north of IB) is sand, and I think it is sandy south of the “delta”

until you get to Point of Rocks Mexico – offshore from the Tijuana bullring.

“If you follow the 3-fathom contour line on the map from north to south, from just north of the Sloughs mouth, you see it change direction from south to southeast. The gradient

there (perpendicular to the contour lines) is fairly steep and points towards deeper water to the southwest, forming the “channel”. The feature we called the channel is really just the deeper water to the south

of the delta. We all called it ‘the channel’, but in describing the area to someone, the word could be confusing…

“The [surfing] areas were called Outside, Middle, Inside, First Notch, Second Notch, Third Notch, Mystery Break, and Backoff.

“The really good surf at the Sloughs is in a very specific location and is associated only with a big clean north groundswell with an interval of 15 to 18 seconds. This swell

breaks in a region called ‘the outside’. The outside is further defined by line-ups as first notch (closest to the beach), second notch, and third notch (farthest out). These notches are features in the hills south

of the Tijuana Bullring (not built until the 1950s) that are lined up with the south edge of the bullring to establish a ‘distance from shore’ estimate. This ‘outside’ region does not indicate any structure

except that the bigger the waves, the farther out they break. The Mystery Break is a break quite a ways outside of the outside break. It always backs off, and is always obscured by waves in the set that accompanies it. We

never seriously considered going out there because it seldom breaks, and it always backs off.

“The outside and the middle are distinguished by a feature that causes a wave that breaks on the outside to ‘back off’ before it re-formed on the middle. The region

where it backs off is called the back-off area. At times the surf is not big enough to break at all on the outside, but there are still good waves in the middle. At other times it breaks on the outside and backs off completely

then re-forms on the middle. When the surf is large, soup from a wave breaking on the outside rolls right through the back-off area, but the shoulder halts its movement southward, recedes northward towards the back-off area

and then re-forms to move south again.

“The tide and the size of the surf determined whether we surfed at the middle or the outside, and often we would start one place and move to the other as conditions changed.

“There is a similar structure associated with the middle and the inside, with another back-off area between them. Thus the question: ‘which back-off area?’ might

come up...”6

“We never got a longitude/latitude fix on the position of the outside breaks,” Jim continued. “The enclosed chart shows a 2-fathom spot, which would be about 2.5

fathoms (15 feet), deep on a medium tide. I think this spot is near the latitude of the outside breaks. It is 700 yards out on the map, and the 3-fathom contour is only about 25 yards further outside. If we assume that a wave

breaks in about the depth of water equal to its height, then the big surf would start about there. With all the fancy electronics available these days, there may be someone with a good longitude/latitude fix on the outside

breaks. I believe the estimate of 1 mile out is an exaggeration, as the map shows a depth of 6 fathoms at 1 mile out on the delta.”7

History of Imperial Beach

As for area names, there are several interpretations of the word “Tijuana.” The dominant interpretation has “tijuan” as a Native American word meaning “by

the sea.”8

The area was certainly inhabited by the Kumeyaay people well before the arrival of Spaniards in the 1700s. After the Spaniards subdued the local people and began to convert natives

to Christianity, the Kumeyaay were noted for their resistance to the conversion.9

Just prior to 1891, there was an active tourist enclave straddling the mouth of the Tijuana River. In 1891, floods destroyed between 30 and 40 homes. When the floods receded, locals

chose to rebuild on higher ground. This search for higher ground is what started the development of the modern-day cities of Tijuana and Imperial Beach.10

Before it was known as Imperial Beach, a land boom hit the area in the 1880s. Promoters followed the general pattern replicated elsewhere. First came acquisition and subdivision,

followed by a hotel or other attraction. Then came land auctions and finally the building of the community by its new residents.11

This same pattern held true for many of the developments in the surrounding area, such as Coronado Heights, Oneonta, Monument City, South San Diego, International City, Barbers Station,

South Coronado, Tia Juana City, and San Ysidro.12

The modern history of Imperial Beach – the Sloughs’ closest population center in the United States – started about June 1887 when R. R. Morrison, a real estate

developer, filed a subdivision map with the San Diego County Clerk. The map referred to the area as South San Diego Beach. The area it encompassed was 5th Street to 13th Street north of Palm Avenue and from about 9th Street

to 17th Street between Palm Avenue and what today is Imperial Beach Blvd. This included areas that have since been annexed by San Diego and which were formerly called Palm City.13

Imperial Beach, 14 miles south of the City of San Diego, “was named by the South San Diego Investment Company in order to lure the residents of the Imperial Valley to build

summer cottages on the beach,” according to the California Coastal Resource Guide, “where the balmy weather would ‘cure rheumatic proclivities, catarrhal trouble, and lesions of the lungs.’ Imperial Beach was a quiet seaside village until 1906 when ferry and railroad connections

with downtown San Diego were completed. After that, a popular Sunday pastime of San Diegans was to board a ferry downtown and sail through a channel dredged in the bay to a landing where an electric train would take them to

‘beautiful Imperial Beach.’”14 Despite these links to the big city, as late as the 1930s and ‘40s, Imperial Beach could still be considered

a “sleepy” town.

Imperial Beach got its first sidewalks in 1909-1910 and a wooden pier was constructed about 1909. The pier’s original purpose was to generate electricity for the town, using

wave action which activated massive machinery on the end of the pier. The “Edwards Wave Motor” ended as a failure and was eventually dis-assembled and removed. For many years thereafter, though, the pier attracted

large crowds, as did the nearby boardwalk and bathhouse. The wooden pier finally deteriorated and it washed into the sea in the severe storm of 1948. The boardwalk lasted until 1953.15

In 1910, the builder of the Hotel del Coronado, E. S. Babcock – who reportedly kept a mistress in Imperial Beach – dredged a channel to where the north end of 10th Street

is today. Boats carrying up to fifty passengers landed at what was called the South San Diego Landing. The boats were operated by Oakley Hall and Ralph Chandler. Captain A. J. Larsen piloted the Grant as it traveled from Market Street, in San Diego, to the South Bay Landing, three times a day. Sometimes a night trip was added. A battery powered trolley car operated by the

Mexico and San Diego Railway Company met the people at the South Bay Landing. The trolley took them up 10th Street to Palm Avenue and then west on Palm to First Street, where it turned left and proceeded to the end of the

street before returning to the landing. The motor cars’ batteries were the newest invention of Thomas A. Edison, who had experimented with a way to do away with the overhead trolley car wires. The cruises were very popular

for about six years.16

A decade after World War II, on June 5, 1956, Imperial Beach voted to become its own independent city. The act of incorporation was recorded in the California State Secretary’s

office on July 18th, 1956. This became the official birthday of Imperial Beach, which became the tenth city in San Diego County and the 327th city in California.17

1937-41

Just prior to World War II, a very small number of pioneering California surfers began surfing south of Imperial Beach, off the river mouth of the Tijuana River. They established

the spot so solidly among Southern California surfers that after the war, The Sloughs became the testing ground for most mainlanders going on to more consistent bigger surf in the Hawaiian Islands. The Sloughs were home of

the then-known biggest waves off the continental United States.

Tijuana Sloughs was first surfed – body surfed, actually – in 1937 by Allen “Dempsey” Holder.

“In the summer of ’37, I went down to the Sloughs and camped with my family,” Dempsey recalled. “Well, I saw big waves breaking out at outside shore break

and went body surfing. I never did get out to the outside of it. A big set came and I was still inside of it. Well, I sort of made note of that – boy, you know, surf breaking out that far.”18

“According to Dempsey,” said John Elwell, a Sloughs rider that would come along in the early 1950s, “Towney Cromwell and him surfed it first [on surfboards] in 1939.”19

“One of the first guys that surfed down here with me was Towney Cromwell,” Dempsey confirmed. “He was studying oceanography at Scripps.”20

For at least the next 10 years, Dempsey rode the Sloughs on the redwood plank surfboards of the time. In the late 1940s, he got a dramatically improved surfboard from Bob Simmons.

“The Sloughs was Dempsey’s place,” Lloyd Baker wrote me. “Every big day with the right swell direction and good wind condition, Dempsey was there. The rest

of us were just visitors, a day here and a day there.”21 A similar parallel can be drawn to the story of Jeff Clark and Mavericks, decades later up the

coast.

“Dempsey was the guru down there,” agreed Flippy Hoffman,22 who rode the Sloughs as a visitor in the late

1940s. What’s more, “Dempsey was surfing there all by himself,” for many years, testified Windansea surfer Jim “Burrhead” Drever, who was one of the early guys to surf the Sloughs, in the 1940s.

“He was really glad to have friends show up to surf with.”23

“Back in the ‘30s and [beginning] ‘40s there were the Hughes brothers,” Dempsey remembered of surfing the inside break, adding that he wasn’t alone

all the time. “They would take a barn door out and would hold it and jump on it in the surf.”24

“He had originally come from Texas, with his family,” Chuck Quinn, who came onto the Sloughs scene in 1949,25

told me of Dempsey. “He started surfing at Pacific Beach, at what was called ‘PB Point’… His mentor, his hero, was Don Okey from Windansea. He said, ‘He was the best. I learned from Okey. He was a genius. He would have been a millionaire, with a little bit of luck,

because he was always inventing things.’

“‘Dempsey,’ I said, ‘Did you and Okey surf together at PB Point?’ He said, ‘Yeah, that was the original.’

“Okey talks about riding 30 and 40-foot waves off Pacific Beach Point,” Chuck repeated to me. “I surfed waves over 20-feet, there,” he attested.26

Chuck might have been exaggerating on Don’s behalf, for as Lloyd Baker underscored, “We surfed the PB Point from 1937 until 1960 and I never saw a wave more than 20 or

25 feet.” Lloyd added, with some humor: “I don’t know what Okey was smoking when he saw 40 footers.”27

“I used to surf with Dempsey Holder in La Jolla, at Windansea,” Woody Ekstrom told me, “and I also surfed with Dempsey at Sunset Cliffs, but mainly in La Jolla.

We’d grab a sandwich, lay down in the park there by La Jolla Cove. It’s something I will always remember – having lunches in the park.

“From there, Dempsey would always come up because Windansea was the most consistent peak of its time. You know, as far as speed and being tough most of the time. You could

always get something out of it.

“Dempsey then went down to Imperial Beach to lifeguard…”28

“What you need to understand,” emphasized John Elwell, who began surfing the Sloughs a little after Chuck Quinn and a good number of years after Woody began down there,

“is that what happened in 1939-1941 was brief. They just sampled it and had boards that really couldn’t surf it. Then, the war broke out and they all went into the military. Dempsey too, but Dempsey suffered a

serious illness and was discharged. He thought it was spinal meningitis.”29

“Our boards were too heavy,” Lloyd Baker, who started surfing the Sloughs in 1940, explained, “and not quick enough to really get the most out of the big thick

waves. Some were chambered redwood, others were balsa and redwood; average 75 to 120 pounds.”30

“It was so primitive,” Woody underscored. “Nobody was there. Dempsey’s the father of the area. Dempsey was the only one who really knew the Sloughs. He’s really the pioneer of the Sloughs… I know the word got out and fellas like Burrhead – Jim Drever, from San Clemente and

Salt Creek – [was one of the first to show up]. And the word got out to the San Onofre area [and those guys came down, also].”31

Winter 1943-44

When the 1940s got under way, Kim Daun joined Dempsey, along with Lloyd Baker, Don Okey, Bill “Hadji” Hein and Jack Lounsberry.32

“According to Kimball [Daun],” John Elwell wrote of one of the Sloughs earliest riders, “surfing was tried again around 1943, when Kimball came back from the merchant

marine once. That is when Kimball was swept almost to the Mexican Border.”33

It ended up being one of the most memorable big days at the Sloughs. It was the Winter of 1943 and World War II was still on in a big way. It was the same season that saw the death

of Dickie Cross in big waves at Waimea.34

“In the winter of ‘43,” recalled Kim Daun, “I was in the Merchant Marine and just come back from a six-month trip. I hadn’t been doing any swimming

or anything, and I wasn’t in the greatest of shape. Dempsey called me and said the surf was up at the Sloughs and wanted to surf with me.”35

“It was so god-damned big that day. So wicked,” declared Bob Goldsmith. “It was one of those days where you could see whitewater forever.”36

“Dempsey and I went out and the shore break was murder,” Kim Daun continued. “Dempsey had a heavy board and my board weighed 90 pounds. We were really a long way

off the beach and we managed to get onto a couple of rides. There was a lull, but then Dempsey and I saw it at the same time: the Coronado Islands disappeared behind swells. So we immediately started paddling out like crazy.

Dempsey was 100 yards north of me and I was on the south side. The first wave broke and I was over to the shoulder of the first wave and it got Dempsey. From that point on I never saw him again.”37

“I was trying to make shore,” explained Dempsey, “but they were so damned big. I was going like hell trying to get back in there and here’s something as big

as a house, looked like it was gonna break on me. I turned around and dove as hard as I could to get in the face of it, and not have it break on me. I don’t know how long that went on.”38

“I got over that first wave,” continued Kim Daun, “and the second one broke about 15 feet in front of me. That wave took my board like a matchstick. My god, when

I saw 15 solid feet of whitewater roaring down on me all I could think was, ‘Get underneath it.’ I finally came up. I don’t know how long that goddamn thing rolled me around. When I came up I was tired. The

next wave busted in front of me again, and I went down and I thought I was deep enough and it still got me and rolled me and rolled me. The next goddamn wave broke right in front of me again, and this time I went down to the

bottom and it was all eelgrass and rocks. I grabbed two big handfuls of eelgrass and that thing just tore me loose from that.”39

“The horizons tilted on me a couple of times, and that scared me,” continued Dempsey. “The next time I didn’t even look around. I just kept going, it broke

on me, washed me far up enough so I could dig in. My eyes had dilated and everything was sort of puffy.”40

From Kim Daun‘s perspective, “Each time these waves came I would swim south as much as I could in the few seconds that I had. The next wave I got far on the shoulder

and I swam south.”41

When Dempsey reached shore, “Bobby Goldsmith shoved my board over to me and said, ‘Where’s Kimball?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, we got separated.

He took off left and I went straight in.’” Dempsey recalled that Daun, “was supposed to be out of shape. I was supposed to be in good shape. I usually didn’t get so tired, but when you don’t have

a wetsuit on, your feet get a little numb, and the eyesight is a little fuzzy. I remember laying across the hood of a car – a Ford convertible – trying to get some body heat in. Bobby kept looking for Kimball Daun.

Couldn’t see him anywhere. Well I said, ‘Goddamnit, maybe he drowned. Who do we let know... we’re the lifeguards, maybe we let each other know.”42

“I just kept swimming south,” retold Daun. “[And then] I was on the beach and they didn’t see me. I came in south of the Tijuana River. I was freezing. I

started walking on the beach and they didn’t see me until I got to the mouth of the river.”43

“We waited there on the beach for Kimball,” remembered Bob “Goldie” Goldsmith. “I hadn’t been worried about Dempsey... old Ironman. I knew he’d

make it. We were concerned for Kimball.”44

“I think I was as close to dying as I ever was in my life that day,” admitted Kim Daun.45

“During those days,” concluded Bob Goldsmith, “it was every man for himself.”46

Dempsey Holder

“Dempsey was just unbelievable,” recalled John Blankenship. “There wasn’t anybody else for sheer guts. He was the ultimate big wave rider. No fancy moves;

he caught the biggest waves and went surfing. The closest guy to Dempsey was Gard Chapin [Mickey Dora‘s stepfather], although Gard never tackled waves as big as Dempsey.”47

“He’d take off even if he had a twenty percent chance of making it,” remembered Buddy Hull.48

“Dempsey would take off on anything, always deeper than he should have,” Buddy Hull recalled,49 and Woody

Ekstrom agreed: “I remember him saying, ‘If you make every wave you’re not calling it close enough.’”50

“Dempsey was as strong as an ox,” Bob “Black Mac” McClendon said, “and he had the guts to go along with it. There wasn’t anything he wouldn’t

try.”51

“I think maybe he was a little masochistic,” declared Don Okey, “he liked to get wiped out.”52

“Dempsey called Towney in the early morning,” John Blankenship recalled of a particularly memorable time Dempsey rounded-up a crew to attack the Sloughs, “and he

[Towney] could hear the roar of the surf in the background.”53

“Towney had gone over the depth charts,” Dempsey said, “and called me up and told me the bottom out there really looks good. I said, ‘Well, I told you about

it.’ And he said, ‘You let me know when it comes up.’”54

“Towney comes up,” added Woody Ekstrom, “and comes out and tells me, ‘Hey Woody, you know that Sloughs is the biggest thing I’ve ever seen on the coast

here. It’s the biggest stuff I’ve ever seen. Dempsey is gonna give us a call when the surf comes up.’”55

“About a week later it came up,” continued Dempsey. “I called Towney and he came down and got a lot of waves. The next day he came back and brought a kid from La

Jolla named Woody Ekstrom.”56

“Dempsey called and was real grave,” added Woody Ekstrom, “and said to Towney, ‘I think it’s gonna be our golden opportunity.’ Towney looked at

me and grinned from ear to ear.”57

I asked Woody what was so funny.

“Dempsey would say, ‘I think it’s our golden opportunity,’” Woody repeated and laughed at the memory. “It was colder ‘n hell and he said

that and Towney looked at me and said, ‘Well, Woody, what do you think of that? Our “golden opportunity”!’ And, God, we were freezing!”58

“They’d get the phone call late at night, ‘Surf’s up,’” wrote environmentalist and local writer Serge Dedina. “The next day they’d

show up at the County lifeguard station at the end of Palm Avenue in Imperial Beach. Dempsey Holder, a tall and wiry lifeguard raised in the plains of West Texas, and the acknowledged ‘Dean of the Sloughs,’ would

greet them with a big smile. For Dempsey, the phone calls meant the difference between surfing alone or in the company of the greatest watermen on the coast.”59

“He would call up –” Woody told me. “I don’t think he could get a hold of me, but he could get a hold of… Towney Cromwell. Towney would [then]

call me up and say, ‘Dempsey called and he says it’s humpin’. Do you wanna go down? Let’s go!’

“What year was this?” I asked Woody.

“1946, ‘cause I remember guys were on 52-20, after the war, you know. The war’s over and all these guys – GI’s – collecting 52-20. Even my brother

was in on that.”61

“Towney and I would get in Towney’s ‘35 Ford coupe – trunk shoved with boards,” Woody continued. “We’d go down there [Imperial Beach] and

meet Dempsey at the Sloughs itself. We’d get on our suits – we had wool bathing suits; like Navy ‘bun huggers’ we used to call them. We’d put on our black wool suits and… it was really cold,

as I remember! Pretty cold. But, the main thing was we had to get out there before the wind came up. Once the wind comes up – and it blows through Imperial Beach quite a bit – by 11 o’clock, you’re

completely blown out.”62

“We had good times together,” Woody reminisced. “Cromwell went to Hawai’i when Dempsey was a ham operator. So, when his wife wanted to speak to her husband

in Hawai’i, she’d drive clear down to Imperial Beach from La Jolla and talk to Towney, in Hawai’i, through Dempsey’s ham radio. Dempsey had the ham operating set-up right in the lifeguard station; about

1948-49.

“Towney and I were just like brothers,” Woody said. “Of course, so was Blankenship.

“He [Towney] got killed June 2nd 1958,” Woody knew the date by heart. “I remember it [the day] real well. One of the saddest days of my life… I still miss Towney…” Woody said quietly, with visible emotion.63

“How long did you surf the Sloughs?” I asked, trying to divert some of Woody’s sadder memories.

“I surfed it until about the early ‘50s. In the early ‘50s, I had to go into the army – in ‘52; got out in ‘54.”64

As time went on and more surfers joined the group riding The Sloughs, the scenario would go like Serge Dedina described:

“Boards were quickly loaded in Dempsey’s Sloughmobile, a stripped down ‘27 Chevy prototype dune buggy that contained a rack for boards and a seat for Dempsey. Everyone

else hung on anxiously as they made their way through the sand dunes and nervously eyed the whitewater that hid winter waves that never closed out. The bigger the swell, the farther out it broke. It was not uncommon for surfers

to find themselves wondering what the hell they were doing a mile from shore, scanning the horizon for the next set, praying they wouldn’t be caught inside, lose their boards, and have to swim in.

“If you liked big waves and were a real waterman,” Dedina summed up, “... you’d paddle out with Dempsey. No one held it against you if you stayed on the shore.

Some guys surfed big waves. Others didn’t. It was that simple.”65

“Dempsey was an ironman,” declared “Goldie” Goldsmith. “He was out there pushing through the biggest, goddamnest shit. He was fearless and brave and

he had the guts. He took off on anything and could push through anything, in any kind of surf.”66

“There was one time when Woody Ekstrom lost his board,” John Blankenship gave as an example. “Well Dempsey grabbed his own board and Woody’s and punched through

the surf.”67

“We didn’t have leashes,” Woody explained to me in that gravel voice he has. “So, if you lost your board, that ended your surfing that day because the swim’s

too far. By the time you got to the beach, due to the water temperature in that area – it’s usually low [in the winter]; 50-55 [degrees F] – by the time you got to the beach, that was the end of your surfing”

that day.68

“One time I lost my board,” Woody said of the time Blankenship had mentioned, “and Dempsey had caught it inside… He got hold of my board by the tailblock.

He had my board plus his. A board in each hand, shoving through these walls [noses first].”69

“We were blown away,” Blankenship attested. “Nobody had ever seen anyone ever do that before. We had enough trouble punching our own boards through the soup.”70

“The biggest wave I ever rode out there was in the ‘40s,” said Dempsey. “I caught one on the outside with that big old board I had. The only reason I took

off on the thing [was] because it looked like there was something else that was gonna break on me behind it. Just barely made it, and before I got to the end, it actually broke over me. I got on the shoulder and straightened

it out. Got down and made one paddle and got in the backoff area. I swear there was one of those big old waves that was as big as the one I’d taken off on. I was scared to death (laughs). I got far enough out on the

end, cut back, got underneath the soup, and rode it till waist-deep water and went into the beach.”71

1st Crew, Early 1940s

· Towne “Towney” Cromwell

· Kimball “Kim” Daun

· Don Okey

· Lloyd Baker

· John Blankenship

· Bob “Goldie” Goldsmith

· Bill “Hadji” Hein

· Jack Lounsberry

Visitors:

· Lorrin “Whitey” Harrison

· Ron “Canoe” Drummond

After The War

“Beginning in the 1940s,” wrote Serge Dedina in a 1994 article on the Sloughs for what was then called The Longboard Quarterly (later just Longboard magazine), “when north swells closed out the coast, surfers from all over Southern California made the journey to a remote and desolate beach within spitting distance of the Mexican border. Before the Malibu,

San Onofre, and Windansea gangs surfed Makaha and the North Shore, they experienced the thrill and fear of big waves at the Sloughs.”72

Even so, only a handful of surfers regularly surfed the Sloughs. While word of the size of the winter surf at the Tijuana Sloughs grew as time went on, visitors from outside were

never large in number. They came from a select group of Southern California’s best watermen – guys like Ron Drummond and Whitey Harrison.

“Back in the early ‘40s I surfed the Sloughs when it was huge,” retold Lorrin “Whitey” Harrison. “It was all you could do to get out. Really big.

We were way the hell out. Canoe Drummond came down.”73

“We paddled out and the surf was probably about 20 feet high or so,” remembered Ron “Canoe” Drummond. “I looked out about a mile where some tremendously

big waves were breaking. I asked if anybody wanted to go out there with me, but nobody did. So I went in my canoe and paddled out there. I set my sights in the U.S. and in Mexico, and figured out where I wanted to be. One

of the biggest sets came through and I caught a wave that was bigger than most. I rode down it when it closed over me. I was caught in the tunnel. Well I rode near 100 feet in the tunnel and just barely made it out. If that

wave would have collapsed on me, it would have killed me.”74

“The main draw back to the Sloughs,” Lloyd Baker wrote me, “was the distance from shore the waves broke [from]. And the temp of the water: 51-58 degrees most all

winter. Because of the temp of the air and water, you sometimes did things that were not too bright.”75

“One big day,” Lloyd went on, “I lost my board on the first wave and it was gone to shore or some place toward shore. It was already cold from the air temp, so

in desperation, I picked up the next wave, which was the largest I had ever tried to body surf. I was so long back in the powerful white water that I was about to dive and give it up. Then, I shot out in front to get a little

air. It finally let me go when I reached the shorebreak. It was nice to catch my breath and get warm again.”76

“The down side of the Sloughs,” Lloyd added, “was the inconsistency (only 4 or 5 times a winter). I lived in Mission Beach and Dempsey would call me if he thought

the next morning might be good. This was fine, but it took 5 or 6 hours out of that day. The time to drive to Imperial Beach, then to get organized and down to the Sloughs, wait for a lull in the shorebreak, paddle out (a

long, long way), catch 2 or 3 waves, then getting warm [on the beach], and back home too exhausted to work.”77

Word continued to spread about the Sloughs, but it was hard to compare to, outside the Islands.

“I had told the guys up north about the surf down here,” Dempsey said. “They were asking about it. One day I stopped at Dana Point on my way back from L.A. with

a load of balsa wood. It was the biggest surf they had there in six years. They wanted me to compare it, and I told them, ‘Well, the backside of the [Slough] waves were bigger than... the frontsides [of the Dana Point

waves].”78

Jim “Burrhead” Drever‘s initial introduction to the Sloughs was not untypical for a good number of Southern California’s best surfers. He recalled, “One time about 1947, I was sleeping in my ‘39 convertible right on

the beach at Windansea, and I heard these guys pounding on the car. I’d heard about the Sloughs and they were going, so I followed them. It was pretty damn big. This was before I went over to the Islands and I’d

never seen waves that big around here.”79

“After the Sloughs,” remarked John Blankenship, the biggest waves at the Cove [La Jolla Cove] didn’t seem so big.”80

“We went out there in the goddamnest stuff,” remembered Bob Goldsmith. “Big stuff – that would scare the hell out of us. The soup was so big that we would

roll over, drive into it with the board, and get thrown around like it [the board] was nothing.”81

“The bigger the better,” added Buddy Hull.82

“When you’re out there you take a different perspective,” said Goldsmith, “because you couldn’t rely on anyone else. You’re on your own. Sometimes

it was just big, cold, and miserable. When it was big we’d say ‘Come on down and hit it.’ But since it would happen in the mornings, me and Dempsey would be down there alone.”83

“I got a board I built for the Sloughs that today sits in the Hobie shop in Dana Point,” reminisced Burrhead. “It weighs about 120 pounds. I put handles on that

board figuring I could get out through the shore break better. I’d launch it and try to get it moving real fast. If I could get my feet on the bottom and give it a big shove and then hang on, the weight of the board

would start [it] going through the waves. You could hang on to the tail, and the board was too heavy to get picked up by the soup. It drew like a drag anchor.”84

“The only reason we made turns,” explained Chuck Quinn, who arrived later on, “was to get an angle and make the wave. Our goal was to ride the biggest waves that

were available on the coast.”85

“When the winter storms came in,” said Bill “Hadji” Hein, “well, people knowing what it was like down there, the first thing they talked about was,

‘Let’s go down to the Sloughs.’”86

Hadji again: “Huge, very huge, and dangerous. Way out to sea. Long paddle. Those were dangerous waves. They were thrill rides. You needed a heavy board. There weren’t

very many guys that liked to go down there.”87

Skeeter Malcolm: “All of a sudden there was nothing and then there were these giant waves.”88

Buddy Hull: “There was virtually no landmark. You really had to be in the right place or you missed it.”89

Woody Ekstrom: “It was always hard to know where to grab the waves. When the sets came, it was really awesome. You didn’t know how far out the next one was gonna break.

You never were able to see it until you got up to the top.”90

“The thing about the Sloughs,” said Burrhead, “was it was so damned big. That’s the reason we went out there. The big deal was trying to catch those big waves.

“During the ‘40s and ‘50s the Sloughs was the closest thing to the Islands. It catches deep water waves that come down the California coast. It’s pretty powerful

because it hits on a finger reef that’s pretty far out and it doesn’t lose a lot of energy.”91

“The hardest thing is to be caught inside,” explained Dempsey. “A big set come in you know the outside is gonna break and its gonna take your board.”92

“One time Dempsey and I were paddling out and got over the top,” recalled Woody, “and here comes Towney off a real WALL, going right – they were rights. The

only thing that was good about it [besides the thrill of the ride] was there was always a channel out there, once you got out through the shore break.”93

“In fact,” Woody went on, “the way I got out was to go into the soup… and out behind the shore break. Because, if you went south [at the start], the shore

break was so big, you’d never make it out.

You’d just punch through and look south and see you’re outside of the shore break, then you’d cut out south and out – toward Mexico.”94

“I can remember when the walls were so big,” Woody said emphatically, “that your heart would go to your mouth. You’d come up over the top and see these monsters. You’d get over the first one – and, you didn’t think you could make it over it, but you did.”95

“I remember one time,” Woody added, “down inside [between two big set waves], one of the surfers let out a war hoop – a yell – and it echoed off the wall!”96

“The tactic for paddling out from the beach was developed by Dempsey and the earlier surfers,” Jim Voit, who came on the scene in the early 1950s, wrote. “It took

into consideration the following:

“The current close to the shore runs towards the south during a north swell.

“The shore break is heavy (very heavy in real big surf) to the south of the channel.

“The shore break is lighter to the north of the channel in the shadow of the outer breaks. The energy of a wave dissipates as it rolls in from the outside.

“The current feeds a rip close to shore in the channel.”97

“The tactic then,” Jim went on, “ is to start well north of the slough mouth, to wait for a lull (there is always shorebreak to get through), to paddle straight

out, letting the current sweep you south, and to maneuver towards the southwest so as to end up in the channel outside of the shorebreak. Woody Ekstrom‘s account of how to get out (The Channel) is accurate.”98

“The tactic for getting in from the outside, with or without your board is different,” Jim made the distinction. “The rip that may help you get out is to be avoided

when coming in. It’s especially important not to get too far south, out of the shadow of the outside break, and into the situation where you must get back to the north, and across the rip, or enter some very nasty shore

break. The tactic is, from the outside, to move towards shore and the channel, then to angle to the northeast towards the middle (some pretty big soup might roll over you), letting the soup help you in, so that you reach the

beach well north of the rip. It’s not an obvious technique, and contradicts ones natural temptation to get south and well away from the big breaks on the outside and middle.”99

“Not having a wetsuit,” Woody declared, “and not having a leash – you had to make all the right moves.”100

“It was cold and we didn’t have any wetsuits,” repeated Burrhead. “If you lost your board it was a big problem. It took you a long time to get in.”101

“By the time you got to the beach you just hung it up and shivered for about an hour,” added Woody.102

“The swims without wet suits were extremely long and numbing,” recalled John Elwell, who started surfing the Sloughs in 1949. “We jumped right back on our boards

and surfed to exhaustion. We burned old tires to ward off hypothermia and watched Simmons eating out of a rough-cut opened can of Soya Beans talking about the surf. Those were the days!”103

The temperature of the winter water added to the distance of the breaks from shore meant hypothermia was a major concern for all surfers prior to the introduction of wetsuits in

the 1950s.

Hypothermia is reduced body temperature when a body dissipates more heat than it absorbs. In humans, it is defined as a body core temperature below 35-degrees Celsius (95-degrees

Farenheit). Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia there is shivering and some mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe hypothermia there may be a paradoxical

undressing, in which a person removes his or her clothing, as well as an increased risk of the heart stopping. Hypothermia is caused by exposure to extreme cold and any condition that decreases heat production or increases

heat loss, like alcohol intoxication, low blood sugar, anorexia or advanced age.104

Sloughs Riders generally surfed in mid-50s degree water for an hour or more, without a wetsuit. Already cold, sometimes they lost their boards a good 500 yards offshore in big surf

and then had to swim in.

Once wetsuits came into common use at the Sloughs, they were discovered to have multiple benefits.

“In the past,” wrote Jim Voit, “when surfing without a wet suit, most swimmers would dive underneath a big break, pause for a few seconds to let the turbulence

die down, and then swim back to the surface, often through considerable residual turbulence. Now in warm water, body surfing with fins in 8-foot surf, this might feel exhilarating – but on a 15+ foot cold winter day

with no fins and no wet suit it was no fun.”105

“After I started wearing a wetsuit,” Jim continued, “the tactic I used when caught inside a big set, or swimming in after losing my board, (no leashes in the old

days either!) was as follows: when a wall of soup rolled over me, I would double up in a ball with my arms protecting my head and neck from loose boards, relax and conserve my energy. I might get pounded if the wave broke

right in front of me, but the buoyancy of the wet suit worked to move me back to the surface. When I started wearing a wet suit at the Sloughs it took a lot out of the fear of getting held under. John Elwell and I also took

to wearing a small inflatable military life jacket that we inflated after the set that wiped us out had subsided. The extra buoyancy made the swim in a piece of cake, comparatively speaking.

“I mention this so we’ll remember that the early surfers here in California didn’t have the luxury of wet suits and were exposed to the double disadvantage of being

cold and being without the life jacket buoyancy effects of a wet suit. I think that the testimonials of Dempsey, Daun, and Goldsmith (Winter 1943-44) are a testimony of the scary excitement of getting wiped out on a big day

and taking the long swim in through big surf. But, those testimonials would not have contained the serious possibility of death from drowning or hypothermia had they all been wearing good wet suits.”106

Another problem was when the fog got thick.

“I remember being out there with Dempsey in the fog,” Woody told me, “and we would hear this funny noise, like the top coming off a wave or something and Dempsey’d

say, ‘What’s that?!’” Woody laughed at the memory. “So, you couldn’t even see too good [sometimes]. Of course, the fog means its glassy [so there was a trade-off].”107

Christmas Time 1949

Jim “Burrhead” Drever addressed the big wave riding of the “Father of the Modern Surfboard,” Bob Simmons:

“I used to say to Bob Simmons, ‘You’re making a big mistake up here [probably San Onofre]. You should go down to the Sloughs – they’re bigger waves.’

He would never believe me. Finally he went down there and he met Dempsey and he hung out down there.”108

Chuck Quinn recalled the first time he saw Simmons, when Dempsey and Simmons first met and Simmons’ moniker of “The Phantom Surfer” began:

“During Christmas vacation, 1949,” Quinn said, “I met Dempsey on the beach near the river mouth. He invited me to go surfing with him. A group of guys were coming

down from Windansea and San Onofre. The next morning we met at the lifeguard station. As we were gathering, Dempsey said a guy had come down there the day before and had a light board tied to the roof of his car. Dempsey said,

‘I told him about the Sloughs and he drove on down.’

“We got down there in Dempsey’s Sloughmobile and saw a ‘37 Ford109 with the back windows painted

out, a board rack screwed to the top, with some quarter inch ropes tied to it. The board was gone and we figured whoever it was, was already out there. It was big that day. Low tide, north swell, and of course, from shore

we couldn’t see it.

“I’d never experienced anything as tough as that shorebreak. So Dempsey said to me, ‘Stick with me and I’ll tell you when we’ll time it and then we’ll

go.’ I barely got through that last wave of set shorebreak.

“It seemed like we were paddling out for half an hour and there was still no sign of anybody. We got out and Dempsey says, ‘Geez, I’m looking for that buoy. I don’t

know where it is.’ Dempsey had put a big buoy on an old engine block to mark the lineup. Eventually we got out to where Dempsey says, ‘The buoy is gone. The surf must have carried it away. Maybe I didn’t

get it out far enough.’

“We’re waiting out there, when all of a sudden we realized there was a huge set coming, and it was way outside from where we were. Dempsey tells us, ‘Paddle out,

paddle out.’ We all started paddling furiously. I had never been in waves that big. These waves were just huge. We got over a couple of waves, but right away half the other guys lost their boards before we even rode

any waves.

“We were struggling, and I was holding on to my board. It’s a wonder it didn’t have hands marks on it. I was really scared and was in a situation that I had never

even imagined. As we pushed through the next to last wave, here came this one lone rider on a huge wave. He was riding steeper and closer to the break then anything we ever imagined.

“After the set we kind of regrouped and we’re waiting for the next big set, when this guy comes out and paddles right through our group. Right into it. No one said anything.

It was just quiet. We had heard about Simmons boards. There was a guy at Malibu that was making light boards out of balsa wood. So I said to him, ‘Say, is that a Simmons board?’ He looked at me and he said, ‘My

name is Simmons and this is my latest machine.’ And I remember when I turned my board I bumped his board. I was just a kid and I apologized. He just kept paddling.”110

“[It was] My first day out in big surf,” Chuck told a little more details of that day. “I’d come down here... before. I borrowed a board from the lifeguards

at North Island Naval Air Station [and] … paddled out [at The Sloughs]; the first time I ever rode a wave on a reef that was breaking [that far] out; first time on a reef made of stones; Summer of 1948.

“There’s a south swell break at the Sloughs. It’s a good little break and it was good for me, because I’d been riding sand busters at the North Island Air

Station with a 12-foot Tom Blake hollow surfboard. I could hardly ever get a ride because it would pearl every time I took off. So, when I got down here [The Tijuana Sloughs], the waves had shoulders on them, cuz there’s

a reef underneath it. I got a wave; a couple of waves.”111

“Then,” Chuck continued, “I bought a board the next summer [1949] over at Windansea… I rode some waves over at Windansea; over 10-feet, with my new board.

Time to go to school. I went up to Villanova Prep School in Ojai. I came down at Christmas, for Christmas vacation. I could see, as I was riding the train down the coast, that the waves were huge. I knew, from what the guys had told me, that this [The Sloughs] was a winter surf place; that Tijuana Sloughs had tremendous waves that broke way out in the ocean on the north

swell.

“So, I came down here in the very afternoon I got back to Coronado. I borrowed my mother’s car and drove down here. When I got to the corner, there, at Palm Avenue, I

saw the lifeguard station. I saw a surfboard laying against the building. I parked my car; took a look at it. It was between 12 and 13 feet long; solid redwood. It had a balsa wood kneeling patch in the center of it, a round

nose and round tail, and it had a skeg on it. So, I knew it was a surfboard [as opposed to a paddle board or rescue board]. I figured it belonged to one of the lifeguards.”112

“I drove down the Slough road and took a walk down to the pipe – there was a corrugated iron pipe. That’s where I’d surfed the summer before. And, as I turned

and started back – it was low tide – I could see the waves breaking way out on the horizon… but, it was afternoon. The sun was getting low. The wind had been blowing all day and it was very, very choppy out there. I couldn’t tell, from the beach, if they were waves that

were ridable or not.

“I was coming back to where I’d parked, at the end of the road. I was walking along the beach and there was a single figure coming toward me.” Chuck looked at me

with intensity. “There’s just something about a waterman. If you grow up around the water, you can see it in a guy. You know. You know he’s a waterman just by the way he walks on the beach. So… we saw each other, about 200-yards apart. We walked right up to each other; nobody else on the

beach; huge waves breaking way out on the horizon.

“So, I said, ‘Are you a lifeguard?’

“He said, ‘Yeah, I’m a lifeguard up at the county lifeguard station at the foot of Palm Avenue.’

“‘Is that your surfboard laying against the station?”

“‘Yep, it is.’

“‘Are these waves ridable? They’re breaking so far out, I can’t tell whether they’re the kind of waves you can ride on a surfboard.’

“‘Oh, yeah! We have to ride in the morning, down here. It’s gotta be low tide. In fact, tomorrow morning, a group of us are going to go out. Do you have a board?’

“‘Yeah, I do.’

“‘Well, you’re welcome to join us.’113

“So,” Chuck went on with his tale, “I hardly slept that night. I put my board on my mother’s car, drove back down here from Coronado. When I arrived, there

were guys – there were 3 or 4 guys from San Onofre and 3 or 4 guys from Windansea: Woody Ekstrom, John Blankenship, Don Okey (I think was the group) and Buddy Hull; guys that I didn’t yet know. I came to know them

later on, but they were guys that I looked up to.

“There was a strata. Surfing was stratified; very elite group. I surfed for a whole year at Windansea before any of those guys talked to me. Finally, one day after surfing

there for a year, one of the guys said, ‘Nice ride, kid.’ So, when I saw those guys down here [at The Sloughs], all of a sudden I was a little rookie. In ‘49, I was 16 years old and these guys were the established

surfers on the [south] coast…”114

Chuck had also surfed up at San O before. “John Elwell and I went up to San Onofre in ‘49, in the summer, with Lee Thompkins, who was head of the lifeguard service in

Coronado. So, I knew who these guys were, but I didn’t know them personally.”115

“So, Dempsey right away came over to me, to make me feel at home. He said, ‘Put your board on that truck over there.’ He had made a kind of beach wagon. It was

just a flatbed with an engine on it. It had a bucket seat that he sat in and he’d made the flat bed out of 2-by-4’s and driftwood that he’d picked-up. The purpose of that truck was to haul boards down to

the Sloughs.”

“Those boards were heavy. They were solid, except for a few hollow boards like the Tom Blake board that I’d borrowed from the North Island Air Station. The boards were

solid; either balsa and redwood or, like Dempsey’s, was solid redwood. They were heavy. Once he said you could put your board there, I knew I wouldn’t have to carry it over those sand dunes at the end of the Slough road.”116

“So, I just hung close to Dempsey and I listened to him. He was talking to the guys from Onofre and he told ‘em, he said: ‘A guy came down here early this morning

and asked directions to the Tijuana Sloughs. He was driving an old Ford. He had a board on top of it.’ He says, “I think it was a Malibu Chip.’ We didn’t know much about the light boards [that were

just coming out for the first time], except from what we’d heard – heard guys talking about ‘em. There wasn’t the mobility that there is, now. Guys didn’t travel up and down the coast like they

do, now. So, we didn’t know who this guy was. Dempsey didn’t know who he was. He just said he’d asked directions to the Sloughs.”117

“So… we got in the Sloughmobile… down to the end of the dirt road, down there by Conrad’s shack… We had to wait until the offshore breeze stopped. There’s

always an offshore breeze in the winter, blowing off of the Sloughs, out to sea. We didn’t have wetsuits and the offshore breeze would make us cold. So, we would wait until the offshore stopped. Soon as the offshore

stopped, the ocean was glassy; no wind. And that’s when we went out. That would be around 7:30-8:00 o’clock.

“So, Dempsey… told us that he had taken, in the dory, a large buoy – a steel buoy – that had washed up on the beach. It had broken away from its mooring.

He painted it white, fastened with a cable to a V-8 engine block used as an anchor. He rode it out to what he thought was the outside reef.

“The problem with surfing the Sloughs was that it breaks so far out in the ocean, when it’s big, that it’s very hard to tell where the next wave is going to break.

So, the line-ups are difficult. It’s hard to get situated in the right place. And there’s always the possibility of getting caught inside and these big waves would take our boards all the way into the beach. There

were no leashes on surfboards in those days. If you lost your board, you swam into the beach to get it. That meant you were frozen. That was the end of your surfing [that day], because [after] the swim in from the outside

reef of the Sloughs, you were too cold to be able to surf any more.”118

“So, anyway,” Chuck continued, “Dempsey said, ‘There’s a buoy out there, but I can’t see it.’ By that time, we were waxing our boards and

getting ready to go out. All the time, Dempsey was looking and he said, ‘I don’t know where that guy is.’ We saw his car and we saw there were ropes for hanging [a board], on either side of the car…

his board wasn’t on his car. We couldn’t see him. It’s such a big scale – the waves were stacked-up between the beach, the shoreline, and the outside reef; about a mile.

“So, Dempsey took us down by the corrugated iron pipe...”

“The pipe,” John Elwell clarified, “was a WW II radar marker, it was huge and could be used as a line-up on moderate days. Dempsey did figure out some line-ups,

after the war, on the Tijuana foothills, off the La Playa, which was Point of Rocks then. He had three notches. Also, as Jim Voit said, we used the control tower at Ream Field as a marker a mile out to sea in this maelstrom.”119

Chuck continued: Dempsey “told us... ‘You have to wait for a lull. We have to time the shorebreak.’ The shorebreak is the last energy that’s in the wave.

It gathers up what little steam it has, after coming across that huge reef, and it breaks in very shallow water. It breaks very, very hard. The shorebreak, in the wintertime down here in big surf, is over 10 feet. So, you

have to time it. They’re hard waves, breaking top-to-bottom and they’re breaking in shallow water, maybe 4-5-6-7 feet deep. Bad situation for those heavy boards. So, you wait and you wait and you wait. When you

think there’s a lull, you grab your board and run and paddle as hard as you can to get out the shorebreak. When you get out to the shorebreak, then there was a channel on the south end of it and you had clear paddling

from there on.”120

“So, our whole group got out to the shorebreak. They were all good surfers. We got out to the outside and still never saw a surfer and we never saw the buoy. So, Dempsey said, ‘I don’t know where the buoy is and I don’t know where that guy is, but I think we’re

out on the outside reef.’

“Sets were about 15-to-20 waves in a set and there was a long time between sets; maybe a half hour. Other waves would come through, but they weren’t the big, big waves… So, we paddled over and we were waiting in a group. Then,

Dempsey saw big waves way, way out; way out beyond where we were. We thought we were out on the outside reef, but we weren’t out far enough. So, he told us, he said, ‘Paddle south and paddle out!’ So, we

all started paddling as hard as we could. These waves [coming] had whole, long crest-lines on them. You could see that they were coming. They were like marching soldiers, like an army.”121

“So, as hard as we paddled, we just barely got over the first wave and barely got over the second wave. Third wave broke and took half the group. They lost their boards. That wave took their

boards all the way into the beach. On about the 8th or 10th wave – as we were struggling to get out, pushing through the surf and holding on to our boards as hard as we could – all of a sudden, we could see there was a lone

rider coming across this huge wave; probably a 25-foot wave. Then he rode across in front of us and we got through that wave. We finally got out and regrouped.

“Dempsey apologized. He said, ‘I thought we were out far enough. But we weren’t. You never know, down here.’ It’s a very gradual reef. The reef was

formed by the flooding of the Tijuana River and it spread an alluvial fan of river stones out in a great arc, from the mouth of the river. And the mouth of the river constantly changes, cuz it would get dammed up by the big

waves and then the water would build up in the Tijuana River and form the Tijuana Sloughs. So, when it got high enough to go over the dam, it would all rush out again. But, it didn’t always go out in the same place.

It’s a wild beast down here. It’s a wonderful, wild place.”122

“So, when we regrouped – those of us that were left – ” Gunker continued, “a set came and we all got some rides and paddled back out again. By that

time, this guy – this lone rider – came paddling back out. And he paddled right through our group, without looking up, without saying anything. He went out beyond where we were; about another [40 feet]... Then, he stopped and started looking out to sea.

“I was going to school north of Los Angeles and I knew some of the guys from LA and I’d heard about these ‘Malibu Chips.’ They called ‘em chips ‘cause

they were shaped like potato chips; front end was turned up, back end was turned down. That was Simmons’ innovation. So, I paddled over to him and I said, ‘Say, is that a Simmons board?’ And he looked at

me with utter disdain. He said, ‘My name is Simmons and this is my latest machine.’ Then, he shifted his gaze out to sea.”123

“We all rode a couple more waves,” Chuck recalled, then, “we regrouped on the beach. You’re all very cold when you come out of the water. No wetsuits. We

used to get these 100% wool swimsuits – the old fashioned kind – that had tops like underwear. They had double-thickness. They were made out of wool. Some of them were Navy issue. They said ‘USN’ on

them. You had a double-thickness over your lower thorax. It’s dark color, either navy blue or black and that would absorb the radiation from the sun and you’d get a certain amount of warmth from that. Wool provides

heat, even though it’s wet. That’s one of the reasons why people wore swimming suits like that in the early part of the century. We could get them at Goodwill or Salvation Army. We’d look for ‘em. That

was the standard swimsuit at the Tijuana Sloughs: old fashioned swimming suits made out of wool, that gave off a little bit of warmth.”124

“So, here’s what happened,” Chuck continued. “We got back up to the lifeguard station. Simmons was there. He wasn’t a talkative guy at all. But, he

and Dempsey started a conversation. He said that he’d been coming down the coast and he’d surfed out at the end of Point Loma by himself; way, way out in the ocean. And, he’d heard about the Sloughs and wanted

to try it. He was stoked. He was really stoked. Ekstrom and Blankenship and Buddy Hull and the guys [from Windansea] and the guys from San Onofre – Jim ‘Burrhead’ Drever and a couple of other guys –

we were all stoked. It had been a wonderful experience [that day].

“We were sitting there on the south side of the lifeguard station, absorbing the sun’s reflection off the white paint of the lifeguard station. By that time, the wind

had come up. There’s a little bit of a lee, there, from the wind. We talked. Simmons and Dempsey became friends at that moment.”125

John Elwell remembered the board Simmons was riding. It was a “dual fin, concave with four slots, and eleven feet long. Later it showed up with rope handles to roll through

the massive soup. I was not there that day because I was just a learner and did not have a board yet. I borrowed boards... I was down there right after that and met Simmons and saw the board. It was out of this world. It was

like Buck Rogers had landed. It was so radical and so different that we thought he was some kind of way-out guy. Everyone there had planks. We begged him for some boards and he eventually made us all boards reluctantly.126

After this, “Simmons used to show up at Windansea,” recalled John Blankenship, “and tell everyone, ‘If you guys had any guts you’d be out with us at

the Sloughs.’”127

“We called him ‘The Phantom Surfer,’” wrote Elwell, “after his incredible appearance and performance” that Christmas time day in 1949.128

2nd Crew, Later 1940s

· Dempsey Holder

· Towney Cromwell

· Don Okey

· John Blankenship

· Jack “Woody” Ekstrom

· Jim “Burrhead” Drever

· Gard Chapin

· Buddy Hull

· Skeeter Malcolm

· “Black Mac” McClendon

· Vern Dodds

· Bob Campbell

· Jim Lathers

· Dave Hafferly

Visiting surfers to the Sloughs, during the 1940s, included: Gard Chapin, Peter Cole, Richard Davis, Bill “Hadji” Hein, Matt Kivlin, Jack Lounsberry, Harry “Buck”

Miller, Preston “Pete” Peterson, Joe Quigg, Dave Rochlen and Tommy Zahn.129

Jim “Lathers paddled out,” John Elwell told me, “but was never considered a surfer. Hadji and Lounsberry only surfed it a few times in the ‘40’s on

planks. Baker, Okey, and Cromwell were the better surfers. They were not seen in the late ‘40’s and there after. Cromwell was killed in a plane crash in Mexico. Baker went into business and tennis. Okey went to

Cal Berkeley.”130

Early 1950s

“So then, later on,” Chuck “Gunker” Quinn told me, continuing his recollections of Bob Simmons, “he came back. He didn’t come back right away...

He talked about the Ventura Overhead… Simmons came back in… ‘51-’52.

“In the meantime, Dempsey went up to Southgate, which is an area in Los Angeles, to General Veneer Manufacturing Company, and he bought balsa wood for all of us; for myself,

for Jim Lathers, for Jim’s brother Richard and Richard’s best friend Vern Dodds…

“So, we made five Simmons copies. We had looked at his board. Dempsey had talked to him long enough to understand the theory of what he was trying to accomplish in his shapes, so we made ‘em. We didn’t have a Simmons board to copy.

We just made ‘em from having seen the board one time and what Dempsey knew, already, from talking to him. We made five boards. Dempsey, myself, Jim Lathers, Richard Lathers and Vern Dodds.”131

“So, we rode those boards,” Chuck continued, “down at the Sloughs that season of ‘50-’51 and it wasn’t until later on – ‘51-’52

– that Simmons came down again. He came in the summertime and he was surfing a lot at Windansea. He started shaping boards for [a few select friends on the south coast]… First board he made was for Dempsey. Then,

he made boards for some of the guys who were lifeguarding here, then; Jim Voit (from Coronado), Tom Carlin, Johnny Elwell, Johnny Elwell’s girlfriend Margie Mannick – those two boards, Margie Mannick’s and

Tom Carlin’s, were smaller. To me, they were among the most beautiful boards that I ever saw that Simmons made.

“The board he made for Dempsey was beautiful, too. It was 12-feet long. It was made from balsa wood that Dempsey got from rafts that drifted up. The Merchant Marine had rafts

made out of balsa wood. Sometimes they’d get torn off ships in storms. Dempsey salvaged the wood. It was a beautiful board. Simmons made a board for me, which I rode from ‘52 to probably around ‘57.”132

“Did you and Simmons become friends?” I asked.

“Well, sort of. He was a guy that you really didn’t become friends with. He was very, very much of a loner.

He would talk to a few people. Bev Morgan was a very close friend of his. Bev was a genius on the level with Simmons. Dempsey had the quality of genius. If a guy was really sharp and really intelligent, Simmons would talk to ‘im.

But, the average guys on the beach, no. He was always thinking about something else. Guys would always come and bother him with questions,” Chuck laughed, then imitating Bob Simmons‘ gruff speech, with falling

pitch:

“‘I d-o-n’t k-n-o-w !’ You know. And he’d walk off.”133

“I got to know him,” Chuck said of Simmons, “and I got a few good rides on his board and he said, ‘I like the way you’re riding my board.’ I guess

that’s about as good a friend as a guy could be with him.”134

On the subject of the way Simmons spoke, I asked Tom Carlin – who, in the estimation of some of his old time Slough buddies, does the best Simmons vocal imitations –

about Simmons’ particular speech. He denied that he could do a good Simmons imitation and then said that Simmons’ speech was a “Gruff way of talking. Kind of not in character with your image of an engineer.

I mean, it wasn’t like he was using bad language… He’d be preaching a little bit. He’d get excited about trying to change certain things…” Then, Tom did a number of respectable Simmons imitations:

“‘It’s a dis-ass-tor!’ He’d be throwing his arms up… very emphatic about what he was trying to get across…

“‘It’s a wipe-out!’ He’d screech and yell.

“‘No Good!’

“The terms he was using weren’t specifically used at that time by, you know, all the surfers. He was driving the vocabulary…”135

“I always got along with him very well,” Woody Ekstrom told me. “In fact, the last day – Simmons’ last day [1954] – I went up to Bob and he was

eating a vanilla ice cream, sitting on one of those stumps in the parking lot and I said to him, ‘Why don’t you join us for a North Bird Rock?’ He said, ‘This [Windansea] is good enough for me.’

“So, when I came back [from North Bird Rock], right away, guys had found Simmons’ towel on the beach and [his] board’s hanging in the shack and ‘We can’t

find Simmons.’ So, Don Okey and I started looking up and down the beach, in the water. Bev Morgan was the fella that [had] brought him down there. Bev was looking all over [too]…”136

Dorsal Fins

“SAN DIEGO UNION – October 9, 1950: A man-eating shark tore a chunk out of the thigh of a 31-year-old swimmer off Imperial Beach yesterday morning in what may be the

first shark attack on a human ever reported in local waters.”137

“We had an El Nino kind of condition during the summer of 1950,” Dempsey recalled, beginning the story of the first known shark attack on a surfer in California.138

“The water was really warm, and there was a south swell – southern hemisphere swell. Made for some beautiful surfing.

“Bob Campbell, Jim Lathers, Dave Hafferly and I went down to the Sloughs,” Dempsey continued.

“Bob and Dave were bodysurfing, Jim had an airmat he wanted to try

out there and I took out my surfboard. I was the first one out. The other guys were real slow in coming out. They were at least fifty yards behind me.

“All of a sudden I heard Bob Campbell holler something. Then Jim Lathers hollered, ‘Shark.’ [Then] Bob hollered, ‘Shark.’ He had a real frightened tone in his voice. I was sitting there on my board thinking that he come out here for

the first time in deep water and he saw a porpoise go by and just panicked. ‘Boy,’ I thought, ‘He’s going to be embarrassed… he really hollered.’ Jim hollered at me again. It was a shark.

I went over there but I didn’t see the shark. There was blood in the water and Bob grabbed Jim’s airmat.

“I put the board right underneath him and took him in,” Dempsey went on. “Got bit – I’m sure he pulled his legs up – he had marks on his hands.

He said it got him twice. Jim Lathers saw it. He said it looked like two fins and then it rolled over. We didn’t take long, everybody was close to shore. I took him in on my board. He was bleeding from his legs. We took

him to see Doc Hayes; he had a little office in the VFW.

“Bob looked kind of weak,” Dempsey remembered. “… he had that gray look. That shark must have taken a chunk of his leg the size of a small steak.”139

“We had always regarded the specter of death as a big dorsal fin,” summed-up Dempsey.140

Another “dorsal fin” incident was retold by Dempsey to Serge Dedina. It was of a time when Simmons and Buzzy Trent surfed the Sloughs with him and some killer whales

cruised by. Based on Chuck Quinn’s recollections, this must have been sometime during the winter of 1951-52 or one of the two that followed. It’s also possible that either Dempsey or Dedina confused the story somewhat,

as Jim Voit also remembers a killer whale incident, but it involved Buzzy Bent, not Buzzy Trent, later in the decade.141 Dempsey’s story as told to Dedina

goes like this:

“Bob Simmons drove all the way down and he brought Buzzy Trent. So I went out. We got on the outside, sat out there a little bit, and a wave came along. Trent caught it and

rode through the backoff area and then got his lunch somewhere in the shorebreak. His board ended up on the beach and he ended up swimming in.

“Simmons and I sat there talking, not really expecting anything. Well, we’re sitting there, I’m looking south, and two big fins come up – one big one and

one not so big. They were killer whales and were about fifty yards from me. Scared me so bad I didn’t say anything to Simmons; he hadn’t seen them. I didn’t want to make any noise at all.

“I’m sitting there on my board. I’m not sure if Simmons saw anything until they went underneath us. Before I could do anything, the little boils come up around

us. I remember my board rocking just a little bit. I looked straight down at the bottom. One of them passed directly beneath my board. We were only in 15 feet of water. I just saw parts of it. The white spots appeared, moving

pretty slowly. Boils come up around. Simmons looked around and saw something. I remember him being profane – he was really excited about the size of these things. I wanted him to shut up. I hadn’t said anything.

I’m still alive. I could see that big dorsal fin. Then the boil disappeared.

“I was still alive and I began to swivel my head around. I could see them fifty yards away or so, going straight out to sea. We relaxed a little bit. A little later Trent came

back out and we told him what had come by there. He turned right around and went back in. Then Simmons and I looked at each other and went in.”142

“The Killer Whale incident,” Jim Voit wrote me, after reading the above, “is either an incident that I wasn’t aware of, or it has been distorted somehow.

Here is an incident that I was personally involved in:

“Dempsey, myself, and Buzzy Bent (not Buzzy Trent) were surfing at the Sloughs sometime in the late 50’s or early 60’s. It was a nice day and the surf was breaking

on the outside. We had come down in the lifeguard skiff, anchored in the deep water to the south of the break, and paddled about 100 yards north into the takeoff area.

“We were waiting for a set and talking, when we noticed what Dempsey speculated were two Humpback whales close to the skiff – in fact they seemed to be examining it.

After less than a minute they submerged, then re-surfaced heading directly towards us. Their dorsal fins, side by side in perfect frontal view, identified them as Killers. We lay quietly on our boards as they submerged again,

passed directly beneath us – the white patches on their sides showing clearly – and continued northward.

“We quit surfing for the day, paddled back to the skiff, and returned to the lifeguard station after alerting two body surfers who were swimming out from the beach.”143

“Buzzy Bent was the most talented Wind’n’Sea (La Jolla) surfer of his time,” Jim added. “He was one of the founders of the Chart House restaurant chain.

I did not know Buzzy Trent except through his reputation as a Hawaii big wave rider...”144

Miki Dora

Jim “Burrhead” Drever recalled at least one day at the beginning of the 1950s, at Tijuana Sloughs, when Gard Chapin brought his step son Miki Dora along. Dora was still

very much a kid:

“There was a day out there when Mickey Dora lost his board. We used to figure Mickey Dora was kind of a crybaby. This was when he was kind of little. He wanted everyone to

do everything for him. He was crying all the time. If he came in and was cold he wanted whatever you had. He wanted you to take care of him. We were all used to having this lousy swim and he wouldn’t swim in. He finally

cried so much that one of our old friends took him in.”145

Coronado Lifeguards

“Around ‘47, ‘48 we met a guy named [Dick] Storm-Surf Taylor,” recalled Coronado lifeguard John Elwell. “He said, ‘Go down and see Dempsey if

you want to start surfing.’ Dempsey was known as the guy who would take off on big waves. He’d been down at the Sloughs since 1939.”146

“Storm Surf was there,” Elwell clarified, “but according to [Kimball] Daun, never surfed it. Dick was in the entourage and not a good water man.”147

“I started working as a summer lifeguard at Coronado… in 1949,” Jim Voit wrote me fifty years after the fact. “During the years prior to 1953, I surfed at

Sunset Cliffs on the old planks and paddle boards. Sometime during this period, we became aware of the winter surf at Imperial Beach, and made our first contacts with Allan (Dempsey) Holder – the San Diego County lifeguard

lieutenant assigned to [the] lifeguard station at Imperial Beach.”148

“In 1949 all the early birds were gone except Dempsey,” Elwell explained.149 “Simmons showed up

with modern boards and the activity and quality of riding picked up. The Coronado surfers were the most active down there as Dempsey’s followers,” mostly because they lived close to Imperial Beach, were good in

the ocean, and Dempsey hired them as lifeguards. “Myself, [Tom] Carlin, Chuck [Quinn], [Jim] Voit were there. [Jim] Lathers was a lifeguard who really did not surf but tried it and was a witness to the history.”150

“Lathers paddled out a few times,” Elwell detailed, “but was never considered a surfer. He never surfed out in front of the station to practice or would go to Sunset

Cliffs and Windansea with us. He was a lifeguard and friend.”151

“I started going with the older guys like Johnny Elwell,” Tom Carlin told me of his participation. “We started to go to Point Loma and Sunset Cliffs [first].

“We would go surf Windansea in the summertime.”152

“The great thing was that Dempsey was here lifeguarding,” Carlin continued. “He made friends with a lot of the people from Coronado. He used to tell us about the

winter time, when it got big here [Imperial Beach]… it was a place we should see. He was very influential and a driving force in trying to get people to come down and really surf with him and find out how to get to the

Outside Reef. I can’t admire him anymore [than I already do]. It was a really great adventure.’153

“The Coronado guys like Voit, Carlin, myself rode it more than anyone else,” Elwell attested. “There were [other regulars] like Jim Nesbitt and hotshot Navy Pilot

John Fowler from Newport Beach.”154

As for others, “[Bill] McKusick, [Pat] Curren… were from Windansea155… [Rod] Luscomb and McKusick

came over maybe three times,” Elwell tried to pin-point it, when I pressed him on each person’s participation. “McKusick was bringing down foam [core] boards to the Sloughs in 1952 or ‘53.”156

“Bill McKusick,” Chuck Quinn recalled to me, “he’s an old Windansea surfer. One of the best. A real innovator in board design, too. He was building light

boards way back then; just out of balsa wood. No fiberglass; just varnished – short, too. About 8-8 ½ feet long…”157