About the time of surfing’s resurgence at Waikiki, at the beginning of the 1900’s, big changes were going on at Australian beaches along the populated areas of Sydney (New South Wales) and to some degree Melbourne (Victoria). These beaches became battlegrounds over the rights to “ocean bathe”, swim and bodysurf.

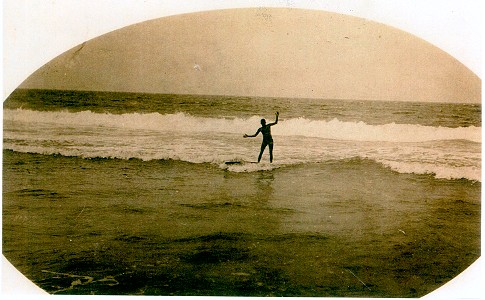

Tommy Walker at Yamba, 1911-12

Photo by Osric B. Notley

First Image of Surfboard Riding in Australia

Restrictions & Bathing Machines

As late as the late 1800’s, getting into salt water for a dip or swim – “ocean bathing” – was still discouraged by the government and society as a whole. Back in the 1700’s, Europeans had considered swimming or bathing in the ocean uncivilized. Many believed that outdoor bathing had helped spread the epidemics that swept England and Europe during the Middle Ages. Consequently, ocean sports got off to a slow start in Australia when Europeans began to settle there.

In the 1800’s, swimming in the ocean off the beaches of Australia was even discouraged by local laws. Legalities relating to swimming were inherited from the English judicial system and code of morality. In New South Wales and Victoria, especially, legal codes were interpreted negatively against ocean bathing.

Surfing Subcultures is a great resource about the early days of Australian surfing. In it, the authors note that “Legal restrictions on open sea bathing appeared first in New South Wales. In 1833, the New South Wales government passed an act (4 William IV, No. 2) prohibiting bathing in Sydney Cove or Darling Harbour between 6 A.M. and 8 P.M. Five years later, another act (2 Victoria II, No. 2, 1838) was passed which extended the surf bathing prohibition. This act banned bathing ‘near to or within view of any public wharf, quay, bridge, street, road or other public resort within the limits of any of the towns... between the hours of six o’clock in the morning and eight in the evening.’ In Melbourne, where the Yarra River had become a favourite place for bathing, a similar act was passed in 1841.”

Despite the fact it was not popular and certainly frowned up, there was still some degree of ocean bathing going on. Otherwise, there would not have been laws against it.

The first drowning of a white person swimming off the beach in Sydney – that we know of – occurred on Saturday, 18 July 1818. Toward the end of that century, transplanted Europeans in Australia began to do away with their prejudices against ocean bathing. The first sign of this was the use of the “bathing machine.”

The bathing machine was first developed in England around 1870. It was a perfect representation of Victorian Era prudishness. England’s Queen Victoria was still on the throne in England, and it was a time of extreme modesty in public behavior in all areas over which the British Empire still ruled. Australian surf champion Nat Young, in his book History of Surfing, wrote of how his country was affected:

“In order to bridge the gap between the Victorian moral code and the desire to bathe in the sea the bathing machine was invented. The English machine, designed to promote modesty and decency, was basically a wooden box on wheels. These so-called machines were drawn by a horse into the sea where its occupants, once they had changed into bathing costumes, would emerge well-hidden by the machine to take the plunge.” A small number of these devices were used on Australian beaches from the late 1870s to the turn of the century.

Australians slowly began to venture out into their part of the Pacific Ocean, laws or no laws. In the Sydney area, “Gradually,” surf writer John Bloomfield wrote, “... men began to explore the joys of sea bathing, until the prudery of the Victorian age produced edicts designed to stop such an indulgence.” As evidence that swimming was gaining greater acceptance, swimming races were included in the Athens Olympic Games of 1896.

“Most people,” wrote Young, “were content to promenade on the piers and the men who pioneered open-sea bathing had to do so before the hour of dawn, as it was illegal to bathe in a public place between 7 am and 6 pm. Bathing often took the form of piling your clothes on the sand and running naked into the surf, where you kept your feet very firmly on the bottom. Not long after the men had begun bathing women took to the sea as well and in 1899 the ladies at Manly, Sydney’s main north-of-the-harbour beach, made a request for dressing sheds; these didn’t materialise for quite a few years because community attitudes had not changed enough to formally condone women bathing. More than one local Manly newspaper was concerned that, if any of the increasing number of bathers drowned, the council would be held responsible. This led to the police patrolling the beach every morning and trying to make sure nobody stayed in the water after 7 am.”

Bathing Attire & Dressing Sheds

Increasingly, in the later part of Nineteenth Century Australia, more and more people were attracted to the ocean. Given the laws against people bathing, swimming or bodysurfing, this brought confrontations between beach-goers and local governments. As an example, residents of Manly and Bondi formed the All Day Surfing Movement in the 1890’s, resulting in some relaxation of bathing hours extended to 7:30 a.m. at Manly. Before 1902, bathing on open beaches was prohibited between 7.30 a.m, and 6 p.m. However, due to strong representation from a growing group of enthusiasts at Bondi, the Randwick Council passed by-laws to allow daylight bathing in November 1902. Other beach side suburbs passed similar bylaws.

Even with the allowance of being able to go into the ocean in the early morning and late evening, codes like Manly’s stipulated that no one was to bathe or swim “in waters exposed to view from any wharf, street, public place or dwelling house...”

Maxwell, in her history of the development of surf life saving in Australia, gave a detailed view of this slow growth of legal concessions: “Notice boards were set up with information as to penalties: up to two pounds for bathing during prohibited periods of the day; up to ten pounds for wearing any costume that did not cover the bather from neck to knee.”

The typical home-made neck-to-knee bathing attire for a woman, wrote Bloomfield, was made “of a material known as gala tea, with embroidered edges, sleeves of elbow length, and the knee portions reinforced with elastic. The fair bathers usually had their legs covered in black cashmere stockings, with bathing shoes below, and a round beret-type hat on their heads.” A typical man’s swim suit was also a neck-to-knee outfit, “with a triangle fore and aft, worn over the costume, and known as ‘vees.’ These were trimmed with colored braid, Manly being blue, North Steyne gold, Bondi white, and so on. Some of the younger bathers, with the idea of being different, bought ‘Canadian’ costumes – two-piece woolen affairs with colored edges. Often an unexpected wave would cause the top half to part company with the lower, exposing a big expanse of flesh, front and back, and embarrassing the wearer.”

“Local authorities turned their attention to dressing facilities near bathing areas,” noted Surfing Subcultures, and this complicated matters somewhat, pitting citizen against citizen. “This concern [by government officials] affected the attitudes of near-beach residents and ratepayers, most of whom objected strongly to beach bathing activities. Enforced funding (via rates) for the provision of dressing facilities for sea bathers added insult to injury in their eyes.”

The numbers of people getting into the ocean increased all along the populated areas of the Australian coast from Coogee in the south to Manly in the north. It was at Little Coogee – Clovelly, one of Sydney’s southern beaches – where bathing by both sexes was first officially approved. “Bathing-sheds were provided for changing,” wrote Bloomfield, “and this led to the consideration of similar demands at other beaches. Manly extended the time of bathing to 8 a.m. and installed a rough enclosure with a lattice top, for men to change in.”

“The first dressing sheds were for men,” noted Surfing Subcultures. “They were open-fronted lattice sheds that faced the sea. Although women began to sea bathe in increasing numbers, mixed bathing was not encouraged. The only mixed bathing around Sydney towards the end of the century was at Little Coogee. This area was not officially classed as a public place. When dressing facilities for women were later established, they were located well away from similar facilities for men; usually at opposite ends of the beach.”

“Mindful of propriety,” the Australian Encyclopaedia documents, “municipal authorities in the early days of surfing attempted to isolate the sexes. Beaches were roped off and signs erected; men to the right, women to the left. Sun baking areas were solemnly marked out.”

Attempts to police the time limits proved difficult, as police on the beach were very easy to recognize. Even when plainclothes police were introduced at the beaches close to Sydney, sometimes they caught the wrong ocean lovers. “In those days,” wrote Young, “it was usual for the crews of the 18-footer racing yachts to sail across the harbor to spend a noisy Saturday afternoon along the Corso and on the ocean beach, and on one occasion it was some of these men that the visiting police arrested. The magistrate practically laughed the case out of court.”

William Henry Gocher, 1903

In 1900, the Commonwealth of Australia was created, replacing direct British rule. Three years later, on the opening Sunday of the Australian surf season of 1903 (first day of September, in those days), William Henry Gocher, editor and owner of the Manly and North Sydney News, went to Freshwater beach, a beach many ocean bathers, swimmers and body surfers frequented. He told the people there that he intended to force the issue of restricted bathing hours and use the power of his newspaper to advance the issue. His intent was to bathe at midday the following Sunday and if the police arrested him, his bathing would serve as a test case and the issue made public. The beaches were the property of the public, Gocher pointed out, not just the ratepayers who had beachfront property and wanted the bathing laws enforced.

Gocher advertised what he was going to do and then went swimming during the taboo hours. Surprisingly, no one got upset or made a big deal out of it, not even the police. Gocher wrote, almost sadly it would seem: “No posse of police came flying down with drawn batons to the waters edge to yell out to me to come out and be arrested. There was no mighty concourse of citizens to cheer me as I came shooting in on a number four breaker, breathing salt, spray and defiance. Outside my few bosom pals... the passing pedestrians took but a tired interest in my plunge for public liberty.”

The following week, Gocher swam again without hassle. On his third and much more publicized entry, Gocher finally succeeded in drawing a crowd. It was a good enough size crowd to dissuade some of Gocher’s friends who were going to join him in the water from suiting up. After a while, the police finally took action, escorting Gocher from the water, questioning him, but bringing no charges against him. It then became obvious to beach goers that the long-standing restrictions were no longer enforced and they were free to enter the ocean whenever they wanted.

It is because of this effort on the part of William Henry Gocher that he is credited for winning Australians the right to bathe and swim in the ocean whenever they wanted to. Research by Pauline Curby, however, indicates that Goucher’s role may be less than previously thought.

Be that as it may, on November 2, 1903, the Manly city council reluctantly decided to allow all-day bathing. “All day bathing was now legal,” Gocher wrote of the scene at Manly, “providing everyone over the age of eight years wore a neck to knee costume.” At Bondi, Frank McEllone and the rector of St. Mary’s church at Waverley had their names taken by police for bathing during the day, but the growing popularity of surf bathing was too much for authorities to stop.

The relaxing of restrictions at Manly started a chain of similar events elsewhere; ones that would lead to the emergence of the surf life saving movement soon to overtake Australia. “Australia’s fascination with the ocean continued to grow through the early part of” the Twentieth Century, wrote Nat Young. “The only setback occurred in 1907 when the mayors of Waverley, Randwick and Manly, in whose municipalities the most popular surfing beaches were located, issued a directive that all bathers, irrespective of sex, had to wear skirts! This was provoked by the fact that men were lying on the beach wearing light, gauzy material which when wet clung to their bodies too closely to be ‘decent!’ The councils decreed that surfers should wear a costume which consisted of ‘a guernsey with trouser legs, reaching from the elbow to the bend of the knee, together with a skirt, not unsightly, attached to the garment, covering the figure from hips to knees.’ The same pattern would serve women as well as men; both sexes had to be covered apron-fashion.”

This ridiculousness was short lived and Manly soon became the center of the Australian surf bathing movement. Even though there were 17 drownings at Manly beach in 1902 alone, ocean bathers and swimmers grew in numbers at a dramatic rate not only there, but at other Australian beaches as well.

Alick Wickham & Tommy Tana

Australian surfing began with body surfing brought to Australia from Polynesia in the late 1800’s, before legal rights to swim in the open sea had been won.

“In Australia,” wrote the authors of Surfing Subcultures, “the origins of surfing were based on body surfing rather than on traditional board riding... the early Australian settlers – mainly of English origin – found no native surfing tradition to encourage or restrict either body or craft-based surfing, as was the case in Hawaii.”

In the 1890's, Alick Wickham, a native of the Solomon Islands, was an important influence in both swimming and surfing. He began by being a major influence on Australian swimming when he demonstrated a “crawl” stroke that was later exported to the rest of the world as the “Australian crawl.”

Around the same time another South Sea Islander, Tommy Tana – a youth employed as a houseboy in the Manly district – was body surfing at the beach there. Tana hailed from the Pacific island of Tana, in the New Hebrides, which is now called by its traditional name of Vanuatu. He amazed onlookers at Manly Beach and inspired others to dive in. His style was studied and copied by Manly swimmers like Eric Moore, Arthur Lowe and Freddie Williams. Williams soon became the first local considered to fully master bodysurfing. Later on, when he became a public figure, he made the first publicized rescue of another swimmer at Manly Beach. Enthusiasm for bodysurfing grew so much that Manly bodysurfers were invited to demonstrate their riding at other metropolitan beaches, ultimately including Newcastle and Wollongong.

During the 1890s, increasing numbers of Aussies took to the sea along the New South Wales and Victorian coasts. As more Australians began to ignore the law and started surf bathing during the day between 7 am and 6 pm, more bodysurfers could be seen along coastal waters. “The irony here,” wrote Nat Young, “is that those Manly families which brought such pressure to bear on the authorities to enforce the daylight bathing law were the employers of Tommy Tanna, and without their bringing an Islander to work in the garden it might have been years before Australians learnt to body surf.”

After the turn of the century, Alick Wickham shaped the first surfboard in Australia. Hand carved from a large piece of driftwood found on Curl Curl beach, this board was so bad it actually sank. Wickham’s knowledge of stand-up surfing using a board was obviously quite limited and is a testimony of how far surfing had fallen in such Polynesian locales as the Solomon Islands by the late 1800’s.

Australian Life Saving Movement, 1903-10

When more novice swimmers and non-swimmers started ocean bathing off unsupervised beaches, accidents became numerous and soon raised public alarm. At Manly Beach alone, there were 16 drownings in the space of 10 years. Local government authorities and regulars at the beaches eventually came to the realization that the general public would need to be either regulated or monitored. This realization became the driving force for the formation of the Australian Surf Life Saving movement.

Interestingly and not unlike today, the increase in surf bathing numbers caused some locals to retreat from popular beaches. For example, some Manly locals began to “escape” to Freshwater Beach, which had first been bodysurfed by Freddie Williams. When the “suburbanites found ‘Freshie’ too,” Fred Notting recalled, “… We used to abuse the living daylights out of those we brought in (rescued). Put them off coming back to “Freshie” pretty often. Suited us!”

One of the first attempts to deal with the drowning problem was made by the Sly brothers of Fairy Bower (Shelly Beach). They set themselves up as an informal rescue organization, after converting an old ship’s lifeboat into a fishing boat and using that for saves. Forerunner to the modern surfboat, theirs was a modified ocean-going modern ship’s longboat, a “clinker style” double whaler, converted to a tuck stern for laying nets. It was powered by four sweep oars.

The Sly brothers – George, Charlie, Tod, Eddie, Joe and relative Neil Norgreen – gave the first surf life-saving demonstration at Manly Beach on December 26, 1903. The demonstration featured “rescues” using their fishing boat and Freddie Williams and other local swimmers as the “victims.” The “Manly Council insisted they wear a uniform, which the brothers looked upon as a bit of a joke. Also they felt the rescue work interfered with their fishing,” wrote Nat Young. “But from their lifeboat developed the Australian surfboat, with its four oarsmen and big sweep oar at the back, which over the years became standard equipment with local surf clubs.”

Surf “lifesaving clubs were to develop into a unique Australian institution,” continued Young, “but their beginnings were unpromising enough. A Life Saving Society had been formed in 1894 and had set up rescue equipment at the most popular Sydney beaches: Manly, Bondi, Coogee and Bronte.” The equipment consisted of a vertically placed pole stuck in the sand with a coil of rope and a circular lifebuoy made of cork attached by a hemp rope. In sizeable surf, this gear was almost useless.

At Manly, a heavy coir line was fixed to large heavy reels that were attached to the bathing sheds. At Bronte, local surfers moved the fixed pole to the most populated section of the beach, only to be condemned for vandalism by the press.

In “Australia and New Zealand,” Surfing Subcultures notes, “early surf bathing was very much a peer group (largely male) activity. It was pursued by groups of persons (often adolescent) skilled in swimming who turned enthusiastically to sun baking and open sea swimming. It seems that in several areas these types of groups existed before the formation of a surf life saving club in the area. It also appears likely that many of the persons involved in these somewhat fringe activities were quite well known (even notorious) in the local community. Although the beach activities of these persons (often involving such things as nude sun bathing) were not condoned by the locals, it was these persons who were frequently called on to perform rescues when somebody was in trouble. There was a degree of tolerance afforded to these groups as a result of this rescue service which was voluntarily performed.” Examples of informal groupings were the Sly brothers and the “Bronte regulars.”

Walter V. H. Biddell, an early supporter and organizer of surf life saving, founded the Bronte Life Saving Brigade in 1903. Biddell also was responsible for the invention of the Torpedo Buoy in 1902, the Surf King in 1906, and a surf boat – the Albatross – in 1907. The Torpedo Buoy was a kapok filled tube attached to a line, the rescuer swimming the appliance to the victim. For a time this method was used as well as the cork filled belt.

Bronte Life Saving Brigade Captain Ted Morrison came up with a shark alarm bell and around 1905 Frank and Charlie Bell tried to ride “a narrow outhouse door” at Freshwater. By this time bodysurfing had become an established feature of beach life and was even promoted on postcards.

In February 1906, Bondi bodysurfers including Lyster Ormsby, Percy Flynol and Sid Fullwood formed the Bondi Surf Bathers’ Life Saving Club. The nucleus of this group came from those who had previously formed a local committee to support St. Mary’s Church rector Frank McEllone, at Waverley, in his right to ocean bathe. The first club house was a tent set in the dunes. The Manly Surf Club would form in September 1907.

“In those early days of surfing,” wrote Bloomfield, “when the beaches had only meager life-saving equipment or none at all, there were many instances of skillful surfers rescuing bathers who had got into difficulties. These rescues often entailed great risks and gradually the surfers who performed them were brought together by mutual interest. They agreed that the methods taught by the Life Saving Society, although satisfactory for still water, were entirely unsuitable for the open sea, and a movement to form surf life-saving bodies grew up. The first to be formed was the Bondi Surf Bathers’ Life Saving Club, which dates from 1st February 1906.”

The following year, in October 1907, the Manly Council installed a professional beach patrolman, Edward “Appy” Eyre, a New Zealander. However, for some reason the concept of a paid lifeguard didn’t work out initially and it was the volunteer surf lifesaving clubs, which handled most all the rescue work.

Surf Life Saving Association of Australia (SLSA)

During this time, surf lifesaving clubs sprang up at Maroubra, Coogee, Bronte, Manly and different beaches in New South Wales. The lifesaving club formed at Bronte in 1907 and Manly’s began in 1908. As the movement started to spread to other beaches, the need for a coordinating body, to promote the most effective methods of rescue and resuscitation began to be recognized. “This came about in 1907, when the New South Wales Surf Bathers’ Association was formed from the various clubs.” It later became known as the Surf Life Saving Association of New South Wales and later still as the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia. It was originally formed from eleven clubs.

“Fairly early in its history, the Association adopted the now familiar motto, ‘Vigilance and Service,’ and the emblem of the life-saver wearing a belt with line attached, watching the surf,” wrote Bloomfield, whose Know-how in the Surf has an excellent short history section on the lifesaving movement in Australia.

The belt, line and reel method was essentially developed around 1906 and was used almost up to present day, with more advanced techniques, equipment and design developed as time went on. “The lifesavers developed their own methods of rescuing people from the surf,” wrote Young, “including the reel-and-belt method... basically, a belt man towing a line makes the rescue and is then hauled back to the beach by other lifesavers manning the reel.” This became standard lifesaving procedure around the world for many years.

The rescue reel actually dates as far back as the 1880’s in Britain. Biddell’s torpedo buoy, to be used as a replacement for the cork belt, was a kapok filled tube attached to a line. The rescuer swam the buoy out to the victim and used it as a flotation device to bring him or her in. For a number of years, the belt, however, was favored over the buoy.

The Bondi Club formed a Lines and Tackle Committee under club captain Lyster Ormsby, Major John Bond (a Royal Australian Medical Corps officer and instructor), and S. Fullwood (Honorary Secretary) to recommend the best equipment for the club to use for lifesaving. Consequently, Lyster Ormsby, Percy Flynn and Sig Fullwood, are credited as the inventors of the “first” life saving reel in 1906. It was initially made from a cotton reel with hair pins. It appears, however, that some type of reel was already in operation at Manly Beach. W. H. Biddell at Bronte used a crude reel attached to his Torpedo Buoy around this time. Complicating the issue of who and what came first, a Mr. Stewart and a Mr. Phillip have claimed they designed a reel for Tammarra Beach, in Australia, pre-1906. Mr. Olding, the builder of the Bondi reel, has also claimed the credit for its design. Bloomfield notes the existence of primitive early reels consisting “of drums ... protuberances on either side, designed to be held in the hands... of the rescue team.”

The reel constructed by coach builders Olding and Parker of Newcombe Street, Paddington, trialed at Bondi Beach on December 23, 1906. The drill was formulated by John Bond. After some modification, it was first used in the rescue of two boys on the 4th January 1907. One of those rescued was Charles Kingsford Smith, later to gain fame as a pioneer aviator. Ironically, the sea eventually ended up claiming Smith’s life in the 1930s, when he and his plane were lost over the Indian Ocean in an historic Australian flight.

According to coach builder Olding, in 1903 a committee of four from the Bondi club, including Ormsby, had visited him. No specific plan or design was formulated, but the Olding reel eventually came about and it was probably originally designed by Lyster Ormsby.

The Bondi reel was adopted by other clubs, most who used a cork filled life-jacket in place of the torpedo buoy. After the various clubs associated in 1907, cork filled belts became standard. Discontinued from modern rescue methods since the 1990’s, the rescue reel still remains as the logo for many Surf Life Saving Clubs in Australia.

Without question, the belt and reel method saved numerous lives during the many years it was implemented as the major lifesaving technique. The reel and line idea quickly caught on in America and elsewhere. As the reel’s use and acceptance grew, so did the Australian surf lifesaving movement which evolved into “a highly skilled and experienced organization with its own carnivals, rituals and sporting culture.”

The Surf Life Saving Association published its first report in August 1909, indicating eleven clubs then active in New South Wales. According to the report, no lives had been lost in the previous twelve months while beach patrols had been operating. Thereafter, similar reports were made with similar statistics even though surf bathing and surfing grew at a dramatic rate across the beaches of Australia. By 1964, there would be 112 clubs operating in New South Wales alone.

The first Surf Carnival was held on January 25th 1908 at Manly Beach. Six clubs competed and the first surfboat race, with various craft, was won by Little Coogee (now Clovelly), using their whale boat. Surf Carnivals quickly become a popular method of revenue for the Live Saving Clubs. The revenue from gate receipts were used to purchase gear and improve facilities. Tamarama Carnival, alone, attracted fifteen thousand spectators in February 1908.

That same year, 1908, possibly in conjunction with one of the carnivals, Alexander Hume Ford – the man who more than anyone helped publicize the resurgence of surfing at Waikiki – visited Manly. He wrote, curiously, that “I wanted to try riding the waves on a surf-board, but it is forbidden.” Around the same time, surprisingly, there was an understanding of what surfboards actually were. It was noted that “Fred Notting painted a brace of slabs and named them Honolulu Queen and Fiji Flyer; gay they were to look at but they were not surfboards.”

Membership of The Surf Bathing Association of New South Wales rapidly extended, and by 1909 comprised nine Sydney clubs (Bondi, Coogee, Manly, Bronte, Bondi Baths, Bondi Social, North Steyne, Little Coogee and Freshwater), two from the South Coast (Helensburgh and Thirroul) and one from the Hunter region (Redhead). In Western Australia, a club was formed at Cottesloe Beach circa 1909. On the East coast, established clubs traveled for demonstrations to metropolitan beaches and as far as Tweed Heads (East Coast Bondi Club).

West’s Pictures, a production and exhibition company, released the first newsreel of a surf demonstration, Surf Sports at Manly in 1909. Pathe Animated Gazette featured a demonstration in Parramatta River, Sydney, by Coogee Surf Life Saving Club members, circa 1910. “It is impossible to over-estimate the impact of such media exposure in this era,” wrote Geoff at Pods For Primates, “the footage would have been shown extensively around the country and possibly screened several times at each venue.”

New Zealand, 1910

From Australia, the surf life saving movement spread throughout the world, most notably to New Zealand, Hawai‘i, Ceylon, South Africa, Great Britain, the United States and the Jersey Islands.

“New Zealand tended to follow the lead set in Australia,” Surfing Subcultures notes, “where most of the life saving techniques were derived. The first New Zealand surf reel from Australia was used in Hawkes Bay in 1910. It was used by the New Zealand Royal Life Saving Society, which took responsibility for early surf life saving rescue and competition in that district, in conjunction with the local swimming association. New Zealand’s first surf life saving club was formed in Christchurch in July, 1910, as a branch of the Royal Life Saving Society in Canterbury.”

Tommy Walker, 1909-1911

Tommy Walker is Australia's first known surfer to ride waves standing up on a wooden surfboard. In a letter to swimming and “surf coach” Harry M. Hay, Tommy wrote: “I… enclose a photo of myself and surfboard taken in 1909 at Manly. This board I bought at Waikiki, Hawaii, for two dollars, when I called there aboard the ‘Poltolock’. I won my first surfboard shooting competition at Freshwater Carnival back in 1911…”

Walker is known to have surfed other beaches besides Manly and Freshwater, notably Yamba on the far north coast of NSW, where he was a member of the Yamba Surf Life Saving Brigade (later renamed the Yamba Surf Life Saving Club).

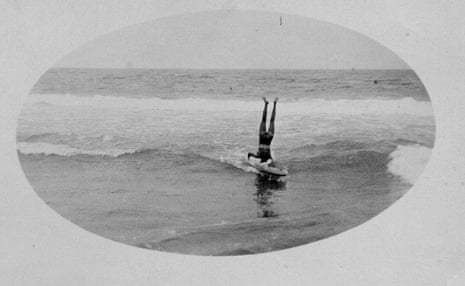

Infact, the earliest known pictures of a surfer surfing in Australia was of Tommy surfing at Yamba in the summers of 1911 and presumably 1912. One of the photos show Tommy doing a headstand while surfing. This ability would be duplicated by many others, as it became a standard showmanship move, particularly during the 20th Century.

And Tommy Walker was “something of a showman, at least according to legend,” wrote writer Russell Jackson in 2017. “Once, charging three-pence a head for a look at his catch, he supposedly swam a hook and the bait of a 7lb salmon straight into the mouth of a 14-foot Tiger Shark at Fairy Bower beach. According to The Referee, Walker and his co-conspirators in the venture had raked in £12-10/- before the council’s “inspector of nuisances” intervened.”

“Another time, while surfing at South Steyne, it was said that Walker would have drowned without the intervention of a local dancer, Ivay Schilling, who swam to the daredevil’s rescue and pulled him to safety. Once resuscitated on the beach, Walker blurted: “Well, that is the last time I’ll go surfing immediately after a heavy breakfast.” Within days the publicity officer of Schilling’s dance company had presented him with a five-pound note for all the media attention the story drew.”

Tommy's real job was as a seaman who worked on the SS Kyogle, regularly traveling between Yamba and Sydney. He spent the winter months in Yamba and during summer head back to Manly.

View image in full screen

View image in fullscreen

C.D. Patterson, 1912

Around 1911, when the North Steyne Club journeyed to Newcastle for a demonstration of surfing and lifesaving techniques, the beachgoers were impressed with the body boarding demonstrated. This was described as “the double banking of Charlie Bell and Ralph Durer on a small board measuring 1 1/2 foot by 1 1/2 foot.” The visiting squad included Edward “Appy” Eyre, Freddie Williams, beltman Rohan McKelvey and The Sly Brothers with their boat.

In 1912, local businessman and politician Charles D. Paterson of Manly brought a solid wood Hawaiian surfboard to Australia on returning from a world tour. This board was once thought to be Australia's first surfboard.

Paterson’s import was a Waikiki revivalist era redwood plank and not a traditional Hawaiian alaia surfboard. First unsuccessfully tested at North Steyne, C.D. Paterson’s Hawaiian surfboard was eventually retired to the family home at the Spit to be used as an ironing board. This historic board is now held by the Australian Surf Museum in Manly.

Also in 1912, the Daily Telegraph reported on the second Freshwater Life Saving Carnival held on January 26th. In the account of the day’s events, there was mention of surfboard riding: “A clever exhibition of surf board shooting was given by Mr. Walker, of the Manly Seagulls Surf Club. With his Hawaiian surf board he drew much applause for his clever feats, coming in on the breaker standing balanced on his feet or his head.”

Following the arrival of C.D. Paterson’s board at Manly, a small group – the Walker Brothers, Steve McKelvey, Jack Reynolds, Fred Notting, Basil Kirke, Jack Reynolds, Norman Roberts, Geoff Wyld, Tommy Walker, Claude West (aged 13) and Miss Esma Amor – began riding on replica boards. Made from Californian redwood by Les Hinds, a local builder from North Steyne, they were 8 ft long, 20" wide, 11/2" thick and weighed 35 pounds. Riding the boards was limited to launching onto broken waves from a standing position and riding white water straight in, either prone or kneeling. Standing rides on the board for up to 50 yards/metres were considered outstanding.

In Queensland, by 1913-14, prone boards four to five feet long, one inch thick, and about a foot wide were in use on Coolangatta Beaches. These were made from slabs of cedar or pine. Charlie Faukner read of Duke Kahanamoku's surf riding and used a board as an aqua planner on the Tweed River, to ride at Greenmount in 1914. Aquaplaning originated from being towed behind yachts on boards around 1900. High speed motor boats were in use on Sydney Harbor as early as 1908.

Sometime slightly before 1914, at Deewhy, “Long Harry” Taylor “made a board resembling an old-fashioned church door, but his efforts in the surf were so futile they became ridiculous.”

Duke Rides Australia, 1914-1915

World War I broke out in 1914, dominating world affairs through 1919 and to a large degree afterwards.

During this time, Duke Kahanamoku had become an international swimming star and took it upon himself to, in his words, “demonstrate [stand-up] surfing wherever there was a satisfactory surf” – such places as the East Coast of the U.S.A. in 1912 and Australia in late 1914.

Duke’s appearances in New South Wales came upon invitation of the New South Wales Swimming Association. After his Olympic wins in 1912, Duke was better known for his record-breaking swimming. Yet, it was Duke’s surfboard demonstrations – not so much the swimming – that really grabbed the attention of Australians and stoked them on surfing. As surf writer Leonard Lueras noted, “The Duke literally pushed that great sea-oriented country into surfing.”

As early as 1914, would-be surfer and writer Cecil Healy primed Australians with the possibility of Duke Kahanamoku coming to Australia to demonstrate his famous Kahanamoku kick.

“Sportsmen everywhere,” wrote surf journalist Matt Warshaw in 1997, “recognized the pure-blooded Hawaiian not just as the fastest swimmer alive and an Olympic gold-medal winner but as an international celebrity. Many also knew him as the world’s greatest exemplar of the newly revived sport of surfing – or ‘board-shooting’, as the Australian press called it. Kahanamoku, whose self-confidence was faulty at best, tended to view himself as little more than a gypsy son of Waikiki.”

“Kahanamoku is a wonderfully dexterous performer on the surfboard,” wrote Cecil Healy, “an instrument of pleasure that Australians have so far been unsuccessful in handling to any degree. Reports have been brought back from overseas of his acrobatic feats executed while dashing shorewards at great speeds, but one doubts the possibility of Duke, or anyone else, duplicating such feats in Australian surf. Still, if he should give one of his rare exhibitions for our edification, be sure it will create a keen desire on the part of our ambitious shooters to emulate his deeds, and it goes without saying that his movements will be watched intently. Personally, I am convinced that the natural amphibious attitude of the Australians will enable one or another to unravel the knack.”

The New South Wales Swimming Association invited Duke Kahanamoku to give a swimming exhibition at the Domain Baths, in Sydney, as part of a 33-race swimming tour. “The country had been at war with Germany since the preceding summer,” wrote Duke’s biographer Joseph Brennan, “and people needed a lift. Duke proceeded to furnish it.” The Hawaiian arrived in Australia on December 14, 1914.

“Kahanamoku arrived in Sydney on December 14 after a 2-week boat trip,” affirmed Matt Warshaw, “and a few days later agreed, when asked by local swimming organizers, to give a surfing demonstration.

Although the “Bronzed Islander” was not technically the first person to bring surfing to Australia – Alick Wickham and Tommy Tana had those honors as bodysurfers as far back as the 1880’s – it was Duke who became the catalyst for the entire surfing movement that would later emerge in Australia.

Duke’s ability to use a surfboard off the coast of Sydney was complicated by the fact that he had not brought along a board and the few surfboards that were around in New South Wales were unknown or deemed unusable for the Hawaiian. So, he made his own board. “Duke was invited by Cecil Healy’s friends,” explained Sandra Hall, “to spend Christmas at Freshwater Beach, a cozy, protected beach with camping huts... While staying there, Duke fashioned a surfboard from pine.”

Patricia Gilmore, an Australian reporter/historian, described what happened, in a nostalgic look back for The Sydney Morning Herald, in 1948:

“Having no board, he picked out some sugar pine from George Hudson’s, and made one. This board… was eight feet six inches long, and concave underneath. Veterans of the waves contend that Duke purposely made the surfboard concave instead of convex to give him greater stability in our rougher (as compared with Hawaiian) surf.

“Duke Kahanamoku was asked to select the beach where the exhibition would be given. He chose Freshwater (now Harbord),” on Sydney’s north side, to give his initial demonstration on surfboard riding. “I was in Australia long enough,” Duke explained, “to build a makeshift surfboard out of sugar pine.” The wood was “supplied by a surf club member,” added Nat Young, “whose family was in the timber business.”

Varying dates are given for Duke’s Australian surfing demonstration. That is perhaps because he made more than one. According to the Sydney Morning Herald of December 25, 1914, it was the previous day, on December 24, 1914, that Duke first rode Australian waves at Freshwater. It is significant to note that a photograph taken there on this day shows several body boards carried by young surfers.

Nat Young recreates the historic three hour demonstration, based on a conversation he had with Isabel Letham, the woman whom Duke rode tandem with that day:

It was “A clear, brilliant day. Spectators were milling around to watch. Manly Surf Boat was on hand to give Duke assistance to drag his board through the break – an offer he laughed at good naturedly. Picking up his board he ran to the water’s edge, slid on and paddled out through the breakers. He made better time on the way out than the local swimmers who escorted him. Once out beyond the break it wasn’t long before he picked up a wave in the northern corner, stood up and ran the board diagonally across the bay, continually beating the break.”

“Kahanamoku entered the water with the board,” wrote the Sydney Morning Herald, “accompanied by Mr. W. W. Hill and some members of the Freshwater Surf Club. Lying flat on the board and using his arms like paddles the champion soon left the swimmers far behind. When he was about 400 yards out he waited for a suitable breaker, swung the board round, and came in with it. Once fairly started, Kahanamoku knelt on the board, and then stood straight up, the nose of the board being well out of the water… On a couple of occasions he managed to shoot fully 100 yards…”

“The Wednesday morning surf check found some passable waves at Freshwater,” Matt Warshaw put it another way. “By 10:00 A.M. the summer sun had warmed the beach, and two or three hundred spectators were lined up along the shoreline, with dozens more settled in on the nearby headland. Kahanamoku arrived at 10:30. He moved across the sand toward the ocean in a standard black, one-piece swimsuit, with his new board resting easily on his right shoulder. Members of the local surf-rescue club, in a sincere but countrified offer, said they’d tow his board through the waves in their surfboat. Kahanamoku said he could manage. The lifesavers nonetheless trailed Kahanamoku as he walked across the wet sand into the surf. Seconds later, paddling through the lines of broken waves, he distanced himself from the local convoy and soon pulled up alone in the calm water outside the surf line. He sat on his board and watched the ocean for a few moments. A swell moved in. He rotated to face shoreward, went prone, paddled, waited as his forward movement was amplified by the wave’s energy, then pushed to his feet. New board, new spot, first time surfing in a month – Kahanamoku set an easy course to his left and simply let the wave push him into shallow water.”

“It was Kahanamoku’s first attempt at surf-board riding in Australia,” printed the Sydney Morning Herald the next day, “and it must be admitted it was wonderfully clever. The conditions were against good surf-board riding. The waves were of the ‘dumping’ order and followed closely one on top of the other… Then, too, Kahanamoku was at a disadvantage with the board. It weighed almost 100 lb. whereas the board he uses as a rule weighs close to 28 lb. But, withal, he gave a magnificent display, which won the applause of the onlookers.”

“There was a big sea running,” wrote Patricia Gilmore, “and from 10:30 in the morning until 1 o’clock Duke never left the water.

“He showed the watchers all the tricks he knew, sliding right across the beach on the face of a wave. Demonstrating the ease with which he could manage with a passenger, he took Isabel Letham (still a resident at Harbord) out with him, and they would come right into the beach with incomparable grace and precision.”

His tandem partner was only 15 years old at the time. Isabel Letham was already a recognized and respected bodysurfer, aquaplanist and ocean swimmer. “When we got onto the crest of this wave,” she recalled later, “and I looked down into the trough, I thought I was going over a cliff.” Letham shouted for Duke to stop and he stepped back to stall. On another wave, Letham again resisted. On the third or fourth wave, Duke ignored her, pressed forward, stood and pulled Isabel to her feet and onto his shoulders. “After that,” she said, “I was all right.” After four waves of going tandem with Duke, Letham was “hooked for life,” she recalled. “It was the most thrilling sport of all.”

While Duke went on tour through Australia’s eastern seaboard and competing in swim meets, Isabel Letham practiced her surfing. When Duke returned to surf at Dee Why Beach before returning to Hawai‘i, she rode with him again, at an exhibition that was widely publicized. She was later inducted into the Australian Surfing Hall of Fame for the role she played in encouraging later Australian generations of women surfers.

Duke recalled to his biographer, in World of Surfing, “In 1915 the swimming-obsessed Aussies wanted to see the so-called ‘Kahanamoku Kick,’ so, along with several aquatic stars, I had the pleasure of visiting that wonderful land of Down Under. The swimming exhibitions went well and we were gratified over the royal treatment they gave us.” While exhibition swimming at the Domain Baths, Duke broke his own world record for the 100 yards with a time of 53.8 seconds.

“When he went to Australia to show them surfing,” Duke’s brother Bill remembered, “the lifeguards tried to stop him. They said, ‘You can’t go out there. There are a lot of man-eating sharks.’ Duke said, ‘Ah, no, I’ll go out.’” After Duke’s surfing exhibition, when he came back to the beach, “the lifeguards asked him, ‘Did you see any sharks?’ Duke said, ‘Yeah, I saw plenty.’

“‘And they don’t bother you?’ the lifeguards asked.

“‘No.’ Duke replied. ‘and I didn’t bother them.’”

“I must have put on a show that more than trapped their fancy,” Duke recalled of his Australian surfing in general, “for the crowds on shore applauded me long and loud. There had been no way of knowing that they would go for it in the manner in which they did. I soared and glided, drifted and side slipped, with that blending of flying and sailing which only experienced surfers can know and fully appreciate. The Aussies became instant converts.”

Duke As Catalyst To Australian Surfing

While on tour in Australia, Duke checked-out other beaches besides Freshwater, Manly and Dee Why because he, in his own words, “was particularly excited by the fantastic surfing conditions they have down there.”

Although Alick Wickham and Tommy Tana preceded him, Freddie Williams is sometimes known as the “Father of Australian Bodysurfing.” Williams went out with Duke on a number of sessions into the surf off the beaches of Sydney while Duke was in the country. On one outing, he went out on a pine board with Duke at Manly Beach. His daughter, Marjorie Sirks recalled, “While they were waiting for a wave quite a distance from shore, to Freddie’s horror, a shark’s fin broke the surface. Duke just waggled his foot at its nose, the way you shoo a cat away.”

Duke’s impact on Australian surfing was tremendous. In effect, he kick-started surfboard riding on the continent. Over twenty years later, in 1939, on the eve of a big Pacific Aquatic Carnival held in Honolulu, then longtime surfboard champion of Australia, Snowy McAlister, wrote:

“We in Australia learned the rudiments of the sport from Duke. He gave the boards new meanings. I don’t think anybody, Hawaiian or Australian, could duplicate Duke’s old time skill.”

Before Duke left Australia, in 1915, he also helped show the Australians how to build boards. “Nothing would do,” he recalled, “but that I must instruct them in board building – a thing which I did with pleasure. Before I left that fabulous land, the Australians had already turned to making their own boards and practicing what I had shown them in the surf.”

“Incidentally,” added Duke, “forty years later, Tom Zahn came to Australia, found my sugarpine board to be still in seaworthy shape. He took it out into the waters of Freshwater Bay and gave the spectator-jammed beach an exciting surfing demonstration.”

Claude West & Duke’s Sugar Pine Board

“Because he was unfamiliar with [our] domestic wood,” wrote Sandra Kimberley Hall of Duke’s Australian board, “he relied on the recommendations of the experts at Hudson’s Timber Yards. Ian Hudson said, ‘Sugar pine was a good choice, because the wood was used for pattern making. It floated easily. It was very expensive, an American import.’“

“Using an adz,” Hall continued, “he shaped the board slightly concave for better lift, rounded the nose, then tapered and squared off the tail. News reports described the board as ‘astonishingly huge.’ It measured nine feet long, two feet wide, and was three inches thick. It weighed 65 pounds.”

When Duke and this board went out into Australian surf, one instant convert was ten year-old Claude West, a Manly beach local. “He was so impressed by what Duke did,” wrote Nat Young, “that he managed to get the Hawaiian to coach him in the art of board riding, and when Duke left Australia he passed the board he had made on to the youngster. Claude soon became a proficient board rider, and other surfers began to imitate him. Claude proved himself a great surfer: he won the Australian surfing championships from 1919 to 1924.”

Then but a gremmie, Claude West’s life was changed forever when Duke gave him his sugar pine board. “Dad worshipped Duke to the day he died,” West’s daughter Maureen Wall said. “Duke talked to him about aloha and Dad tried to share this and teach others.”

Later, West got so adept on Duke’s pine board that one contemporary commented: “He had no equal... he surfaced as though he had suckers on his feet.”

West went on to demonstrate the benefits of the surfboard in surf rescue work and at one point rescued the then Governor-General of Australia, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson. He built many boards like the one Duke had given him and was a fine wood craftsman, “having learnt to fine-plane making coffins for an undertaker.” In 1918, West attempted to make a lighter surfboard by chipping out the center of a solid board and covering it with a lighter wood. The experiment failed, due to the absence of waterproof glue, which had not been invented yet, and the fact that all Australian timber of the period was sun-dried instead of kiln-dried. Consequently, when the sun got to the board, it quickly cracked the thin outside veneer.

“West and his board were invited to demonstrate surfing at lifesaving club carnivals,” wrote Sandra Hall of Claude and Duke’s board. “Getting to these events took ingenuity. If it was a few miles away, West paddled, but if it was further, he traveled by train. The board was stowed with luggage and with coffins, which were sometimes ‘occupied.’

“Surfing caught on rapidly. Although West surfed decades before formal [surfboard riding] contests were organized, he is acknowledged as Australia’s first surf champion. He retired undefeated after a decade at the age of 27. The Australian Surfriders Foundation honored West in 1966 as the ‘first national surfing expert,’ and bestowed its first honorary life membership on him. A longboard Pro-Am competition bears his name today at Manly.”

“The board – which had no skeg or leg rope – had other adventures,” Hall continued. “West rode it into the history books on the Queenscliff Bombora, a tricky break created by submerged rocks. Half a century later, few people have dared it. Midget Farrelly described it as ‘very scary.’

“Duke’s board pioneered Aussie surf rescues also. The powerful lifesaving bureaucracy fought against the use of boards in rescues, insisting on the superiority of belt man and lifeline. In 1923, however, West rescued four swimmers with Duke’s board in monstrous surf that even a surfboat could not negotiate. By coincidence, the local alderman witnessed the rescues and vouched for the effectiveness of boards in lifesaving work.”

“West received many commendations for the more than 1,500 lives he saved,” Hall wrote of the lifesaving Claude West did during his active years surfing, “but he rarely talked about them. What he valued above all else was Duke’s board. He worked on the board every winter, pampering it, smoothing out any rough spots, and lacquering it. Later he added a gold trim and Duke’s name.

“The board retired in 1952. West presented it to the Freshwater Surf Club to perpetuate Duke’s memory. Surrounded by memorabilia and photographs, it became a surfer’s shrine.

“In 1956, Duke returned to Freshwater. He thrilled the crowd by taking the board into the surf. The white-maned legend told West, ‘It’s as good as the day I made it (42 years ago).’

“The next year, the board survived a fire which gutted the club house. The flames were so intense that electric wiring melted. West said it was no miracle the board survived: it was because of Duke’s ‘mana,’ or power, that the board made it through.

“Like any warrior, the board was scarred and dinged. Its worst accident occurred when it fell off a truck in 1975, split down the middle, and was run over. The elderly West restored it expertly.

“As the decades passed, Duke’s board took fewer trips. In 1980, it presided at West’s beachboy-style funeral; in 1988, it was the star attraction in the Hawaii Pavilion at Brisbane’s World’s Fair.”

“The board’s story has a happy ending,” Hall concluded, writing in 1996 for Longboard magazine. “82 years after Duke first showed the Aussies how to surf, surfing is now Australia’s most popular national sport. An incredible 1 in 5 men, and 1 in 10 women, enjoy the exhilaration that fueled both Duke and West. Aussies have racked up more world championships than the rest of the world combined.

“And the board that started all this? It is now insured for $1 million, the most valuable and loved board in the world.”

The Surf, 1917-1918

Little known, the Australians were quick to have the world’s first magazine or newspaper solely dedicated to surf riding, entitled The Surf: A Journal of Sport and Pastime.

“Within 24 hours of its debut on December 1, 1917, the premiere issue of the world’s first surfing publication, The Surf: A Journal of Sport and Pastime, sold out to surfing enthusiasts in Sydney, Australia. First run for the weekly was a very respectable 5,000 copies.”

The publication was a far cry from what we would consider a surf journal or magazine to be, today. However, it was the first and, in format, reflected the style of the day for weekly publications. Its unknown editor’s stated purpose was “to champion the interest of the beaches and work steadily for their protection and development.” As such, he could be considered a very early environmentalist.

“The Surf does not forget that the surfer is a gay-hearted, carefree child of nature, who enjoys the good things the gods have given him,” continued its editor, “and it will, therefore, strive to reflect in its pages some of the gladness that dwells in their hearts.”

Pictures were few and it was text that carried the weekly. Exhibiting the interest male surfers took and would continue to take in females on the beach, The Surf reported on an unidentified Bondi Beach blonde in each issue. “When she took the water last Saturday,” one issue described, “the beach was a panorama of staring eyeballs and open mouths.” The editor referred to her as a “mermaid” squeezed into a swimsuit so snugly that “if it was any tighter you could tell what she had for breakfast.”

To supplement the one-penny cover price, The Surf ran advertisements for tea shops, hotels, houses for rent and land for sale in Sydney’s beach area. It appears that when the editor was short of copy, he also ran a serialized Charles Dickens-style novel, horse racing notes, fishing reports, and theater listings.

Being a Sydney publication with only a local focus, the weekly was so far removed from the surf scene at Waikiki that after several attempts at Duke’s last name, including the classic “Kahanabanana,” the editor gave up trying to spell Kahanamoku altogether. Surfing was more often referred to as “board shooting” and the word “surf” was synonymous with “ocean,” referring to the noun and not the verb.

Irrespective of its limitations, The Surf hit on a number of issues of importance to area beach-goers. The editor covered the restrictions on beach attire and was outraged, once, when a beach inspector confiscated and destroyed two boys’ surfboards when they were swept over into a swimming-only area. Along with addressing real issues affecting those who spent time at the beach, the weekly’s editor also found time to do a good amount of teasing and joking.

With World War I going on at the time, it was inevitable that such a good-times publication like The Surf would not have a long run. The idea was a good one, but the timing was bad. As it is, The Surf managed to publish for five months, shutting down the presses for its last issue on April 27, 1918. The reason seems to have been the lack of imported newsprint due to war shortages. It was the end of the Australian summer and the end of The Surf.